Photo by Fritz W. Schuller, MPA.

TIDES OF CHANGE

Script by Ken Maher, Stories from Another Day, a Collingwood Museum Podcast. Photos courtesy of the Collingwood Museum and Fritz W. Schuller, MPA.

Amidst the hush of anticipation and the roar of a final launch, Collingwood’s shipyard community gathered to witness the end of an era and the uncertain dawn of a future without shipbuilding.

The silence among the crowd is profound, pierced only by a single cough from somewhere off to the side, echoing in the dense quiet. Many have endured the cold for hours, gathered for a moment they had hoped never to witness. They stand together to see the last of its kind. The once bustling activity has quieted; all eyes and ears are now focused, waiting for a signal—the signal that signifies the end.

It’s December 6th, 1985, the launch day for Hull 230, the Sir Wilfrid Laurier. Today, she will be honored as the final vessel to be side-launched in Collingwood, marking the conclusion of more than a century of shipbuilding history in the town. Despite this significant event, the official closure of the Shipyards will pass almost unnoticed, a little over 10 months later, on September 12, 1986.

For well over five generations, through the age of wood and steam to steel and diesel, hundreds of ships came to life at the north end of Collingwood’s main street. Over and over again, in steady progression, mountainous ships took shape to the sound of hundreds of men and women working through every season and all kinds of weather. Among the vessels, Hull 205, the M.S. Chi- Cheemaun, stands out. Launched on January 12, 1974, it remains one of the most iconic and recognizable ships ever built at the Collingwood Shipyards. For over 100 years, the shipyard shaped both the fortunes and the daily lives of families in Collingwood as surely as those tradesmen and craftsmen shaped the mighty hulls.

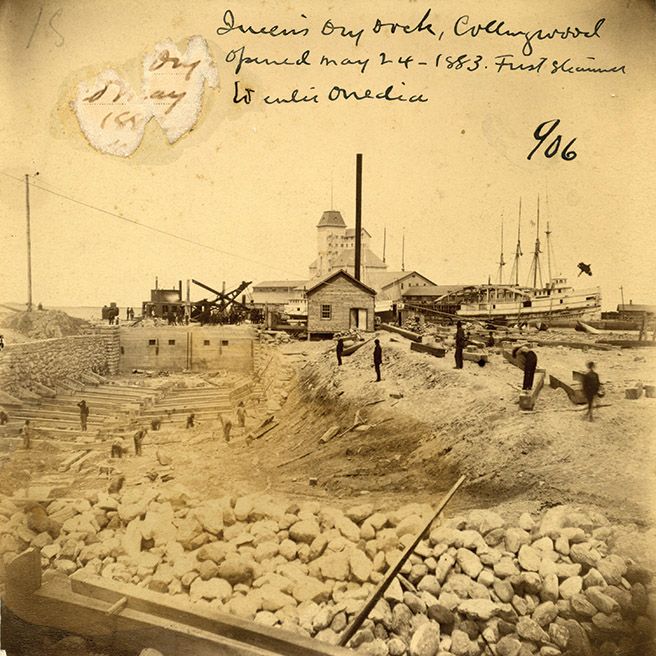

And it all began only a stone’s throw away from this final crowd’s gathering, with a day of speeches and ceremony and hopes for a bright future. That day was May 24th, 1883—a day full of the promise of spring and new beginnings for the Town of Collingwood. “Ladies and gentlemen, most esteemed and honoured guests,” the voice carried over the restless din of the large crowds gathered. “I did not expect the honour of addressing you on this most auspicious day. However, as Mr. Dalton McCarthy has been detained by his parliamentary duties, I shall seek in my small way to offer words, though unplanned, as might befit the occasion.” With a barely perceptible sigh and a groan, the crowd grew uncomfortably quiet. They knew from experience that Mayor Dudgeon’s unplanned remarks were rarely brief. The ceremony had already started late, and many of those gathered had hoped to still go see the horse races already in progress. It was some time past the official start time of 1:30 in the afternoon, and several thousand people were gathered in Collingwood’s harbour—all because of a fire. A fire that had occurred on the deck of a steamer the autumn before. But no one could seem to light a fire under the mayor and move the ceremony along.

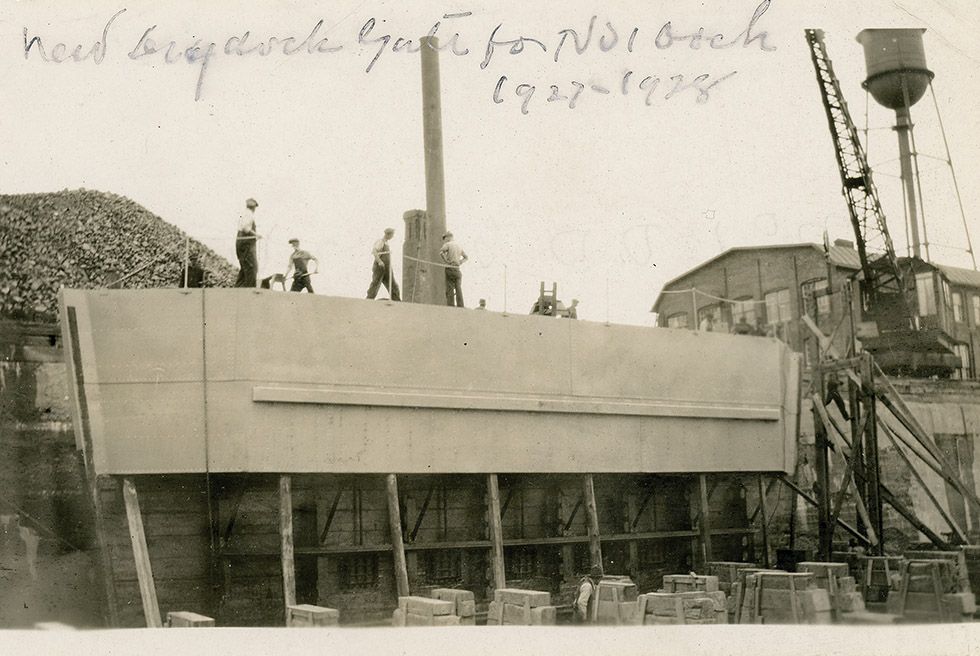

Dry Dock No. 2, added in 1909 at the north end of Hurontario Street, served for around 50 years before being permanently flooded and converted back to a launching basin. Collingwood Museum Collection 002.54.3a

The story of Collingwood’s shipbuilding prowess dates back to incidents like the one involving the Oneida. After winter lay-up, this steamship, running between Chicago and Collingwood, suffered fire damage to its upper decks. Measuring 215 feet in length and weighing 1,070 tons, the Oneida was noted for its exceptional construction—a testament to the shipbuilding standards that defined Collingwood’s maritime legacy. This incident, coming in the wake of the tragedy that befell the steamship Asia, underscores the challenges and triumphs of the shipbuilding industry that Collingwood would become known for… but that tragedy is a story for another day.

On this day, over three dozen dignitaries, two brass bands, and a procession of firemen boarded the Oneida, still showing the signs of fire damage. But today that damage would be fixed— right there in Collingwood at the brand-new dry dock. With the celebration coinciding with Queen Victoria’s birthday, the new dry dock would alternately be called the Collingwood Dry Dock, the Queen’s Dry Dock, and later Dry Dock No. 1.

For well over five generations, through the age of wood and steam to steel and diesel, hundreds of ships came to life at the north end of Collingwood’s main street.

And Mayor Dudgeon, not expecting to speak, did an extraordinary job by all accounts. He went on at great length regarding “the history of the agitation for the dock and its importance to the town.” Over the past few years, the sheer volume of traffic running out of Collingwood necessitated dry dock services. Thus, in 1882, the enterprising Messrs J.D. Silcox and S.D. Andrews formed the Collingwood Dry Dock Shipbuilding and Foundry Company and began construction at a cost of some $40,000. The town gave them a bonus of $25,000 to hurry along the construction. It was built to be 325 feet long, 50 feet wide at the gates, and 60 feet wide between the retaining walls. And the whole length had to be blasted out of solid rock before the sides could be constructed back up in limestone blocks. It also boasted a state-of-the-art Baldwin centrifugal pump which could clear the dock of its water in as little as five to six hours.

The mayor finally finished his speech (which seemed hours long to those missing the horse races) with a flourish and much applause. Following him, Mr. Thomas Long, the former MPP, kept his congratulatory speech to a most pleasant length, and then christened the dock. And with that, the fire was lit that would see vast and important changes to our local harbour.

The Queen’s Dry Dock, pictured during construction before its inauguration on May 24, 1883, sits north of Huron Street, aligning with St. Paul Street’s angle. Presently, it remains permanently flooded. Collingwood Museum Collection, X969.238.1

Work on the dry dock was not yet finished when the Oneida was brought in and the christening took place, but several further projects were already underway. Silcox and Andrews had begun to fill in and level a large space beside the dry dock for a shipbuilding yard. A slip would be excavated, and a wharf constructed. At the same time, the harbour was being improved with a Dominion grant of a further $26,000 to dredge and build a second breakwater running northwest out into the water from the Northern Railway’s elevator. Taken all together, these improvements would also light a fire in the community that would burn strong for a century, making Collingwood’s harbour a focal point of shipping and ensuring in its heyday as many as 1,000 jobs and, directly or indirectly, a livelihood for so many people who would come to live in Collingwood.

But those days were now gone. And now, on this dreary December day in 1985, the final hull having been wedged into place, the staples having been removed, and the command having been shouted, the staccato ringing of hundreds of sledgehammers falls silent. The workers solemnly move back. All the speeches have been made. There is nothing left to be said. And for the first time in a century, no one is upset if they went a little long.

All the ceremonies of a launch day were dutifully fulfilled. The band now stands quieted. The deck crew awaits in their precarious perch on the deck of the ship. And the whole town holds its breath.

And then the signal rings out, and in near unison, dozens of axemen cleave through the triggers. And for the briefest of moments, it seems as if nothing will happen. Then, almost imperceptibly, the ship begins to shudder and slide toward the water’s edge. And with every passing second, it begins to pick up speed, tilting sideways. The mountain of steel careens at an impossible angle, pulling massive chains and enormous drag boxes full of slag with a deafening shriek and a roar. And you can feel its passage in your chest as much as you can hear it in your ears and see it in your eyes. And in a magical moment, the whole thing drops into the water, and a tidal wave churns up everything from the bottom of the bay and sends it surging out in a tsunami of spray. And even though everyone is sure that the ship must be swamped by the waves, it eventually rights itself (as they always do) to float serenely in the bay. And in the space of one or two racing heartbeats, the sound of rushing water and the groaning of metal is buried in the wild and sad cheering of the crowds.

And nobody is ready to leave even long after the waves and the cheering subside. Because they can feel the tectonic shift under their feet. The whole of their community has been building to this day for over a century. And now that it has come, the whole world seems to have shifted to an impossible angle. What will it all signal? How will the shipyard town survive without the shipyard? Will it be swamped and sink like so many industry towns before? What will the people do for work? How will they provide for their families? The questions drag up all kinds of unpleasant doubts and fears. What comes after the end of your way of life? What will shape the community of Collingwood now?

The Queen’s Dry Dock, pictured during construction before its inauguration on May 24, 1883, sits north of Huron Street, aligning with St. Paul Street’s angle. Presently, it remains permanently flooded. Collingwood Museum Collection, X969.238.1

More than ships were constructed by the Collingwood Shipyards. A new gate for Dry Dock No. 1 was completed c. 1927. Collingwood Museum Collection, X969.400.1.

These, and a hundred others like them, are the questions that will take years to understand, much less answer… but today is a day for melancholy celebration. Questions and cleanup are for another day. All that the hard-working people of Collingwood know, as they head back to their homes, is that a well-made ship, carefully launched, will always right itself. This town had been under construction for 130 years. Hard work, dedication, and pride had made her as solid and well-built as any you can find. No matter how far sideways things seem to slide today, she will be just fine. For every beginning must come to an end, and every ending is really just another beginning.

And nobody is ready to leave even long after the waves and the cheering subside. Because they can feel the tectonic shift under their feet. The whole of their community has been building to this day for over a century. And now that it has come, the whole world seems to have shifted to an impossible angle. What will it all signal? How will the shipyard town survive without the shipyard? Will it be swamped and sink like so many industry towns before? What will the people do for work? How will they provide for their families? The questions drag up all kinds of unpleasant doubts and fears. What comes after the end of your way of life? What will shape the community of Collingwood now?

These, and a hundred others like them, are the questions that will take years to understand, much less answer… but today is a day for melancholy celebration. Questions and cleanup are for another day. All that the hard-working people of Collingwood know, as they head back to their homes, is that a well-made ship, carefully launched, will always right itself. This town had been under construction for 130 years. Hard work, dedication, and pride had made her as solid and well-built as any you can find. No matter how far sideways things seem to slide today, she will be just fine. For every beginning must come to an end, and every ending is really just another beginning. E

Welding aboard the MS Chi-Cheemaun, circa 1973. Photo by Fritz W. Schuller, MPA.