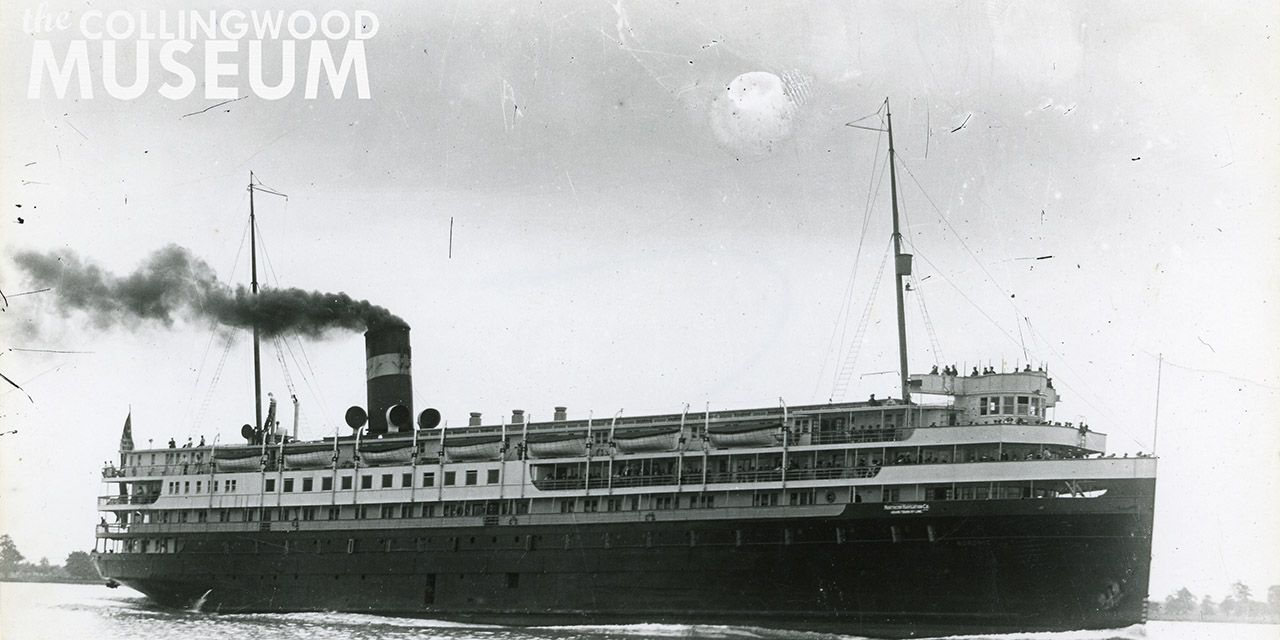

An undated photograph of the passenger steamer Noronic underway, passengers gathered along its decks. Collingwood Museum Collection, 998.3.181.

The Three Sisters

Script by Ken Maher | Stories from Another Day, a Collingwood Museum Podcast

Photos courtesy of the Collingwood Museum

From a history-making launch to two devastating disasters, the tale of Huronic, Hamonic, and Noronic is one of ambition, loss, and an unforgettable Great Lakes legacy—ships whose fates were as dramatic as the era that built them.

Collingwood’s Big Day, as the newspapers reported it, was September 12, 1901. It was the day that changed our shipyard forever and led to generations of prosperity for the residents of our little town. And it all began with a history-making ship named Huronic.

Mr. Calderwood, manager of the Collingwood Shipbuilding Company, had charge of the work on the Huronic from its beginning to its end—and that included the day of her launch. He had planned every last detail so that, as the Barrie Northern Advance described it, at the launch of the vessel “she passed from the stocks without causing the slightest accident of any description.” The christening ceremony was performed at precisely 1:00 p.m. by Miss Long, a close relative of Mr. John Long, the company’s president. As the ship moved from her former bed, a mighty cheer rose from the throats of more than 7,000 people assembled in our harbour to witness the launch of the big steamer, and the whistling of boats in the harbour and the mills kept up a roar for fully five minutes.

But why, you may ask, all the fuss? The steamer Huronic was the largest freshwater vessel ever built in Canada (at that time) and was the very first to be built of steel here in Collingwood. She was also the first of what would come to be known as the “Three Sisters” of the Great Lakes. Although wooden ships had been made here in Collingwood for nearly 20 years already, the Huronic would be given the honour of being named Hull #1. Her successful launch would open the floodgates to steel ship manufacturing and would put the Town of Collingwood on the map as a world-class shipyard. Indeed, immediately following the launch of the Huronic, the keel of the next ship was laid in its vacated space.

It was only after the next hull was underway that a luncheon followed Huronic’s launch, served in the moulding loft. Accounts, again given in the Northern Advance, tell us that about 400 gentlemen were present. Later, the guests—which included the minister of public works, the general manager of the Grand Trunk Railway, former and current members of provincial parliament, judges, mayors, and many well-known names of the day—listened to the expression of hearty goodwill by many of the speakers and prominent people present. When the celebrations were finally over, the honoured guests left promptly at 6:00 p.m. in the same way as they arrived: by a special train provided for the marking of the event.

Two men paddle a lifeboat past the partially submerged hull of Noronic after the devastating fire in Toronto Harbour. Collingwood Museum Collection, 993.3.214.

As the Marine Review proudly noted, the Huronic was constructed of open-hearth steel throughout and was 325 ft. long, 43 ft. wide, and 27 ft. deep. She could accommodate 200 saloon passengers and an even larger number of steerage passengers. A feature of her design appreciated by the travelling public was the elegant dining room, extending the full width of the lower cabin. It was finished in quarter-sawn white oak and full of fine china. The plushly appointed smoking room, also finished in white oak, was at the extreme aft end of the upper cabin. Only the best of the best for those fortunate enough to travel aboard Huronic. The vessel was equipped with two tiers of cabins, one above the other, with a shade deck extending both fore and aft. Deck room was also provided for 700 tonnes of package freight, and the lower hold was divided into five compartments with a combined capacity for 80,000 bushels of wheat.

Fred Landon, a professor at the University of Western Ontario, recalled his time on the Huronic in an interview published in 1968: “I was on the Huronic on her first voyage in the spring of 1902 and I remained with her all that season until she docked at Sarnia on Dec. 14th. I also worked on her while a student in other years.” In all, the Huronic made 15 round trips during 1902—a season marked by much fog and by rough weather in the closing weeks. On Huronic’s final trip of the season, Landon recorded that coming back from Port Arthur, the ship needed to plough through six to eight inches of quickly forming ice on Lake Huron, and when they finally arrived in Sarnia to overwinter, they couldn’t disembark until they took axes to all the ice that had formed on the ship itself. Only then could they open the gangways.

The Huronic would carry—not just in that season but through all its seasons—thousands of passengers over the waters of the Great Lakes, and do so in enviable style. First, she sailed under the Northern Navigation Co. of Ontario, which would be sold to Richelieu & Ontario Navigation Co., which in turn would be merged in 1913 into Canada Steamship Lines of Montreal. But through all the changing times and company names, the Huronic sailed on, and in all her long years on the Great Lakes she only ever had two minor incidents of note.

The Huronic ran aground in the Black Sunday Storm of 1913 just off Whitefish Point in Lake Superior. There was no loss of life, although many other vessels that ran aground during the same storm saw tragedies that still haunt the Great Lakes to this day. The second minor incident Huronic faced was in 1928, when she was temporarily grounded and refloated quickly off Isle Royale in Lake Superior.

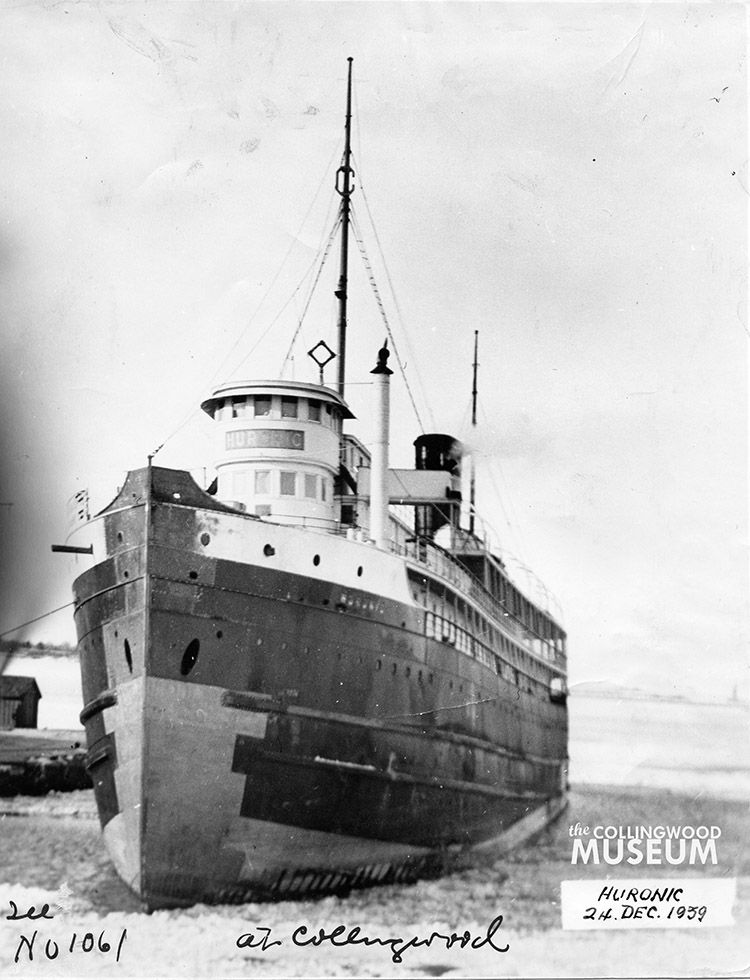

Left: Steamer Huronic overwintering in Collingwood Harbour on December 24, 1939, with ice visible in the water. Collingwood Museum Collection, X968.758.1.

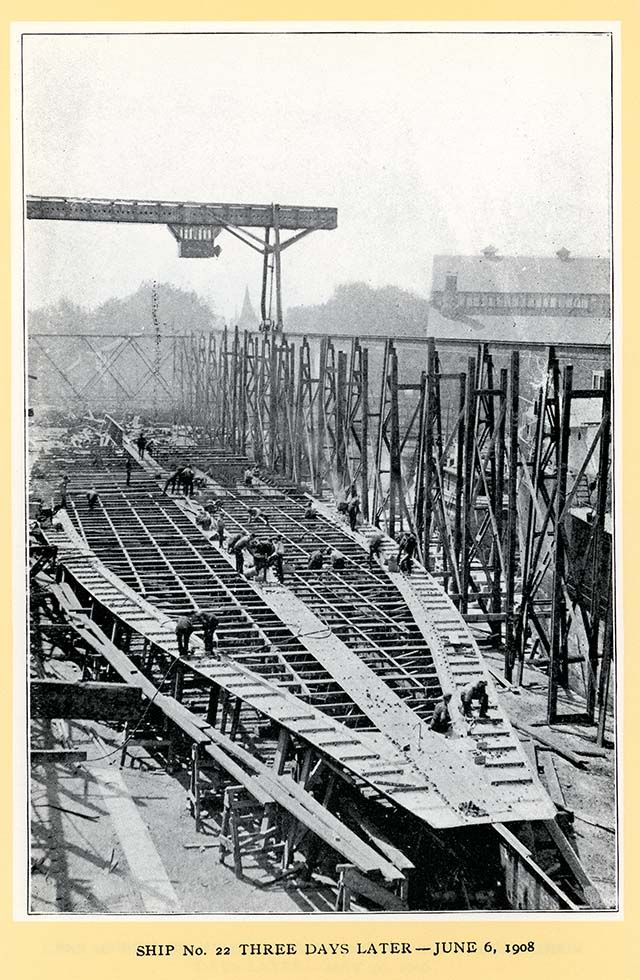

Right: Excerpt from The Building of a Ship showing more than 25 shipbuilders at work during Hamonic’s construction on June 6, 1908.

After almost 40 years of distinguished luxury passenger and freight service, the Huronic retired from passenger service in the 1930s. The upper cabins were removed, and the Huronic continued to sail the waters of the Great Lakes thereafter, serving as a package freighter.

The second of the famous “Three Sisters” of the Great Lakes, the Hamonic, built upon the success of the Huronic, going bigger and better. Also launched at Collingwood—this time in 1909—the Hamonic was described as a well-appointed passenger ship with many facilities, including a barbershop, music room, ballroom, and dining salon with large windows for viewing the passing scenes. Canada Steamship Lines ran a seven-day passenger cruise aboard the Hamonic, from Detroit to Duluth, which included a stop at Sarnia.

Riding a wave of success, the third and final sister, Noronic, would be launched on June 2, 1913, this time out of Port Arthur, Ontario. Constructed by the Western Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Company for Canada Steamship Lines, Noronic was also designed for passenger travel and package freight service, following the tradition of her smaller sister ships. The Noronic, however, stood out with five decks and a length of 362 feet, accommodating up to 600 passengers and 200 crew members. One of the most elegant and sizable passenger vessels in Canada at the time, Noronic earned the nickname “The Queen of the Lakes” and was considered the Three Sisters’ crowning jewel.

The Hamonic’s sailing career would end suddenly on July 17, 1945. As the Sarnia Journal records, the Hamonic had docked at Point Edward around 5:00 in the morning, and most of the passengers were still asleep at 8:30 a.m. when a truck making a delivery to the freight sheds caught fire. The fire spread quickly to the tinder-dry sheds and soon embers were raining down over the Hamonic. Within minutes the entire ship was ablaze. Unable to use the lifeboats, passengers and crew jumped over the side to avoid the quickly spreading flames. Captain Horace Beaton rushed to steer the ship away from the burning sheds and ran her hard aground. Ropes were lowered for people to slide down.

As the same newspaper records, a crane operator for the Century Coal Company named Elmer Kleinsmith saw the blaze, fired up the crane, and used the bucket to move passengers and crew to safety. Miraculously, all 350 people aboard survived. The same couldn’t be said of the Hamonic. She burned to a total loss. And it would be only the first disaster to befall the Three Sisters.

Colourized postcard showing the launch of Hamonic in Collingwood on November 26, 1908. At the time, it was the largest passenger steamer built in Canada. Collingwood Museum Collection, X2010.47.1.

As recorded by the Museum of the Order of St. John in Ontario, only four years after the Hamonic’s ordeal, on the night of September 16, 1949, the Noronic was docked at Pier 9 in Toronto Harbour (the approximate present-day location of

the Toronto Islands ferry terminal). At 2:30 in the morning, a fire was discovered in a locked linen closet and quickly spread throughout the ship. Five hundred and twenty-four passengers were onboard at the time, but of the 171 crew members, only 15 were onboard. This resulted in what can only be described as a very poor evacuation.

The scene would later be described is one of great panic. After only 20 minutes,the ship’s hull was already turning white from the heat of the blaze, and the decks were beginning to buckle. After an hour of fighting the fire, the Noronic was so full of water from fire hoses that she started to list toward the pier. By 5:00 a.m., the “Queen of the Lakes” was a smoking ruin. The recovery effort was so difficult that the death toll would only ever be estimated at between 119 and 139.

An inquiry was formed by the House of Commons to investigate the tragedy, seeking answers for the horrifying loss of life. Some blame was laid upon the negligence of many of the crew, while the company argued that it was a matter of arson. None of the ship’s fire extinguishers were in working order at the time of the blaze. Further, it was determined that the design and construction of the 36-year-old ship were also at least partly at fault. The very posh interiors that drew so many passengers—well, they became part of the problem. They were lined with lemon oiled wood instead of newer fireproof materials. Adding to the tragedy, passenger exits were only located on one of the passenger decks instead of on all five. Damage suits for the Noronic were settled for just over $2 million.

Taken together, the disasters of the two latter sisters effectively sealed the fate of the first. Call it guilt by association (or by common design): the Huronic, even though she had only been hauling freight for many years, was unceremoniously retired just a few short months after Noronic’s catastrophic fire. The Huronic was sold for scrap to the Steel Company of Canada. The pride of the Collingwood Shipyards sailed in December of 1949 to Hamilton to be scrapped in 1950.

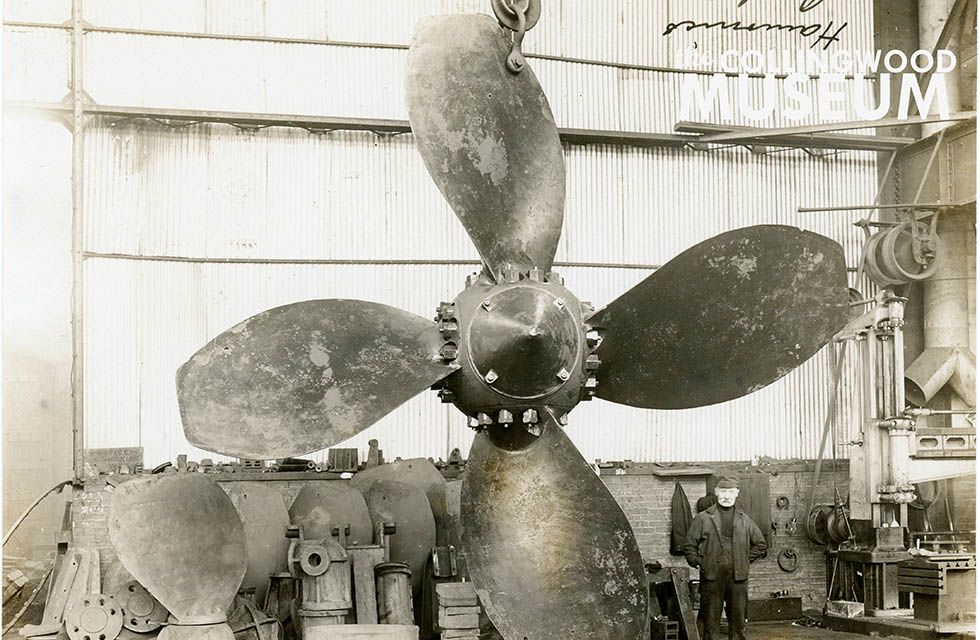

The scale of Hamonic’s propeller is evident in this photograph of an unidentified man standing beside the lower blade on October 20, 1908. Collingwood Museum Collection, 2020.2.1.7.

Yet consider this: in those 50 years of the Huronic’s service, the steel shipbuilding legacy she began here in Collingwood had continued to grow through the World Wars, with some 145 further hulls—from lakers and bulk carriers to tankers, tugs, trawlers, corvettes, and minesweepers for the war efforts. And the history of any one of those ships would make a captivating tale. But each of these is most certainly worthy of a story for another day.

Today we remember that even shipyards go the way of old ships eventually, and so it was that 85 years after the Huronic’s historic launch, the rat-tat-tat of the riveters’ hammers in the Collingwood harbour fell silent and the name of the Huronic was in danger of being forgotten…

…forgotten, that is, until two local families decided to form Collingwood Charters. Their flagship purchase would be a vessel bearing the name of that historic Hull #1: Huronic. And it is their aim to use the 65-foot tour boat to showcase Collingwood’s rich marine heritage, showing residents and visitors alike the beautiful sights that have enthralled Great Lakes passengers since the days of the luxury steamships and the Three Sisters—only now, Collingwood Charters does it with the added onboard experiences of local music and events, private charters, and their popular sunset and sightseeing cruises, all while using the very slipway that saw the side launch of so many fascinating ships built and repaired right here in our Collingwood Shipyards. E