Words by Cara Williams – Photos by Clay Dolan

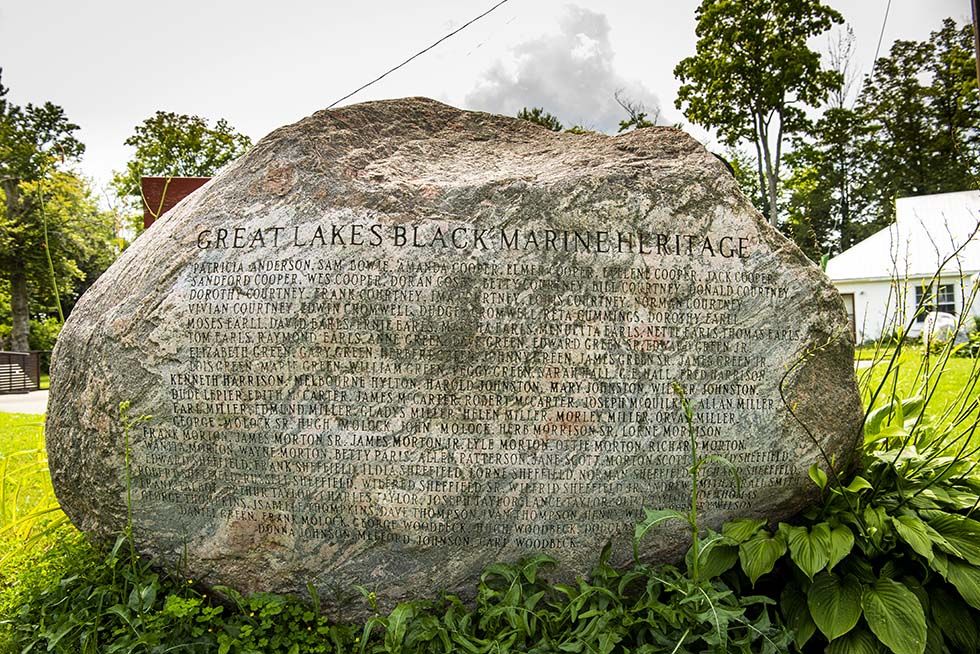

In the early 19th century, nearly 40,000 Black Americans escaped slavery in the southern United States by travelling to Canada through a complex, clandestine network of safe houses known as the Underground Railroad. The largest anti-slavery freedom movement in North America, water played a tremendous role in aiding freedom seekers. In Upper Canada, the Great Lakes became the main terminus of the Underground Railroad, providing critical opportunities for employment and homesteading.

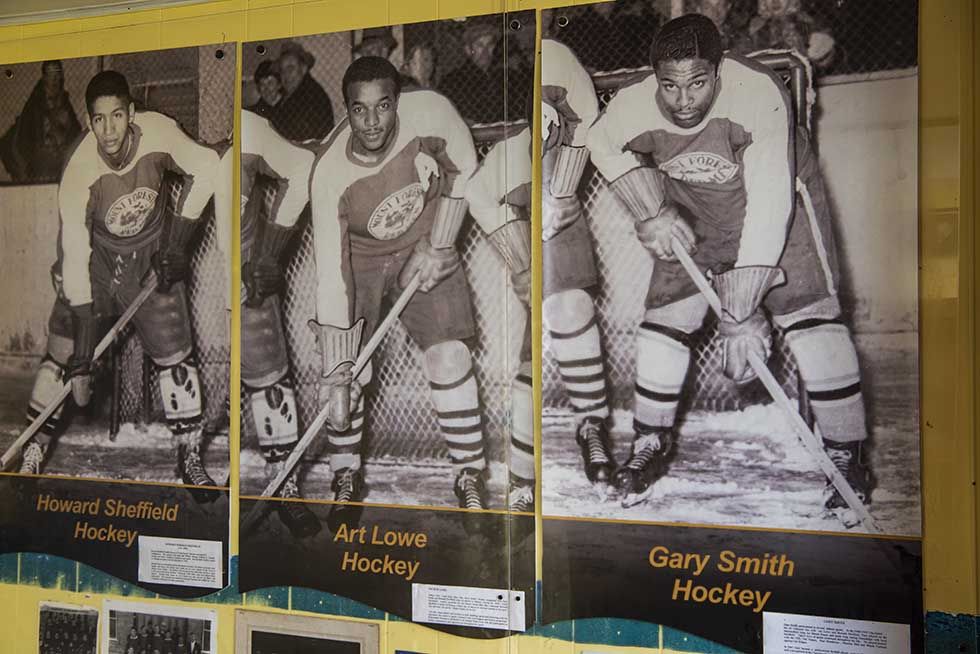

Carolynn and Sylvia Wilson, whose ancestors were some of the first to settle in Collingwood in the late 1700s, are co-owners, curators, and caretakers of Sheffield Park Black History & Cultural Museum in Clarksburg. Originally established in Collingwood, Sheffield Park was the vision and dream of the sisters’ late uncle Howard Sheffield who sought to gather, preserve, and share the history of their Black ancestors. Today the homespun museum sits on a generous plot of land in The Blue Mountains. Sixteen outbuildings display artifacts, exhibits, and treasures and take visitors on a journey through Africa to the early Black settlers of the Great Lakes. The vast collection merges Sheffield/Wilson family heirlooms with community donated artifacts and thoughtfully reshapes how Black history is communicated within domestic and local contexts— some exhibits invoke inspiration and awe, while others summon agony and despair.

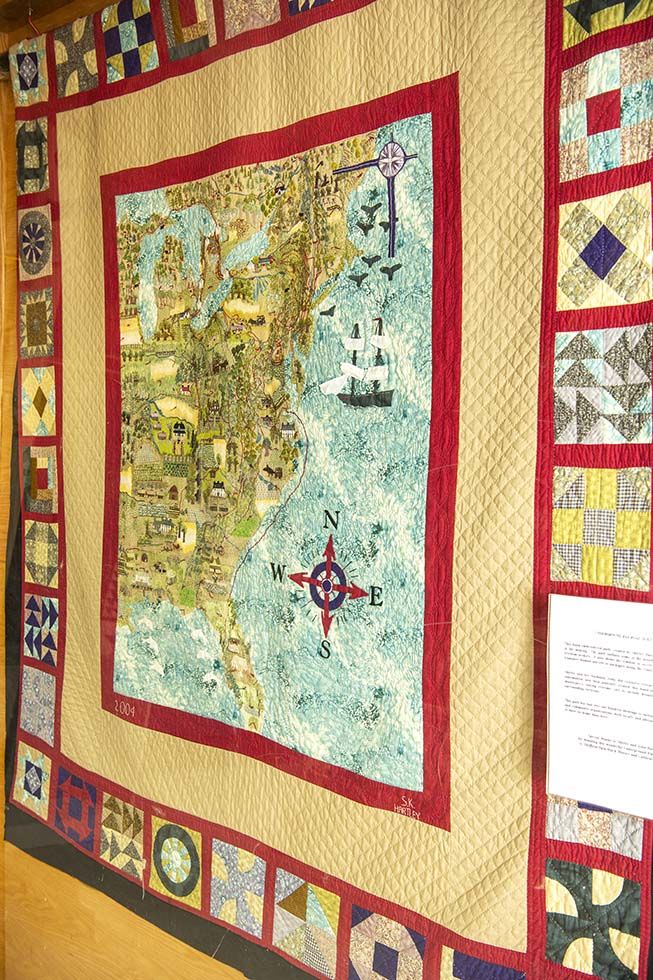

Displayed in the museum is a magnificent embroidered quilt stitched and donated by Shirley and John Hartley. This work of art painstakingly outlines the route that slaves travelled towards freedom and is a reminder of the plight of freedom seekers. As Sylvia explains, the Underground Railroad was named as such because the abolitionists behind the safe house network used railroad terminology and symbols to mask their activities. “Conductors (abolitionists) would send or receive parcels, dry goods, or packages (Black men and women) to arranged destinations (safe houses). Various means of escape were used, either by foot, in wagons with false bottoms, or physical disguises. Messages were conveyed in songs such as ‘Follow the Drinking Gourd,’ ‘Way Over Jordan,’ or ‘Down by the Riverside.’ Freedom seekers crossing the border into Canada found refuge in various settlements throughout the province. Many settlements were stop-off places or terminals on the Underground Railroad, with Collingwood and Owen Sound being the two most northern terminals.”

In the early 1900s, shipbuilding was an essential industry on Lake Huron and Georgian Bay. These waterways were an economic lifeline that linked communities like Collingwood, Thornbury, and Owen Sound. Working on the Great Lakes ships allowed Black workers to extend their connections and family relationships in various waterway ports. Black entrepreneurs established their own businesses, catering to the needs of the Black community. Many became professionals, while others opened schools for apprenticeships. Constructing models of wooden steamboats often built by or worked on by Black settlers became a hobby for Richard Sheffield in the early 1900s. Many years later, his grandson, Eddie Sheffield, would continue this craft. Several of their impressively ornate, hand-crafted replicas are on display in the Abolitionists House and Great Lakes exhibits at Sheffield Park.

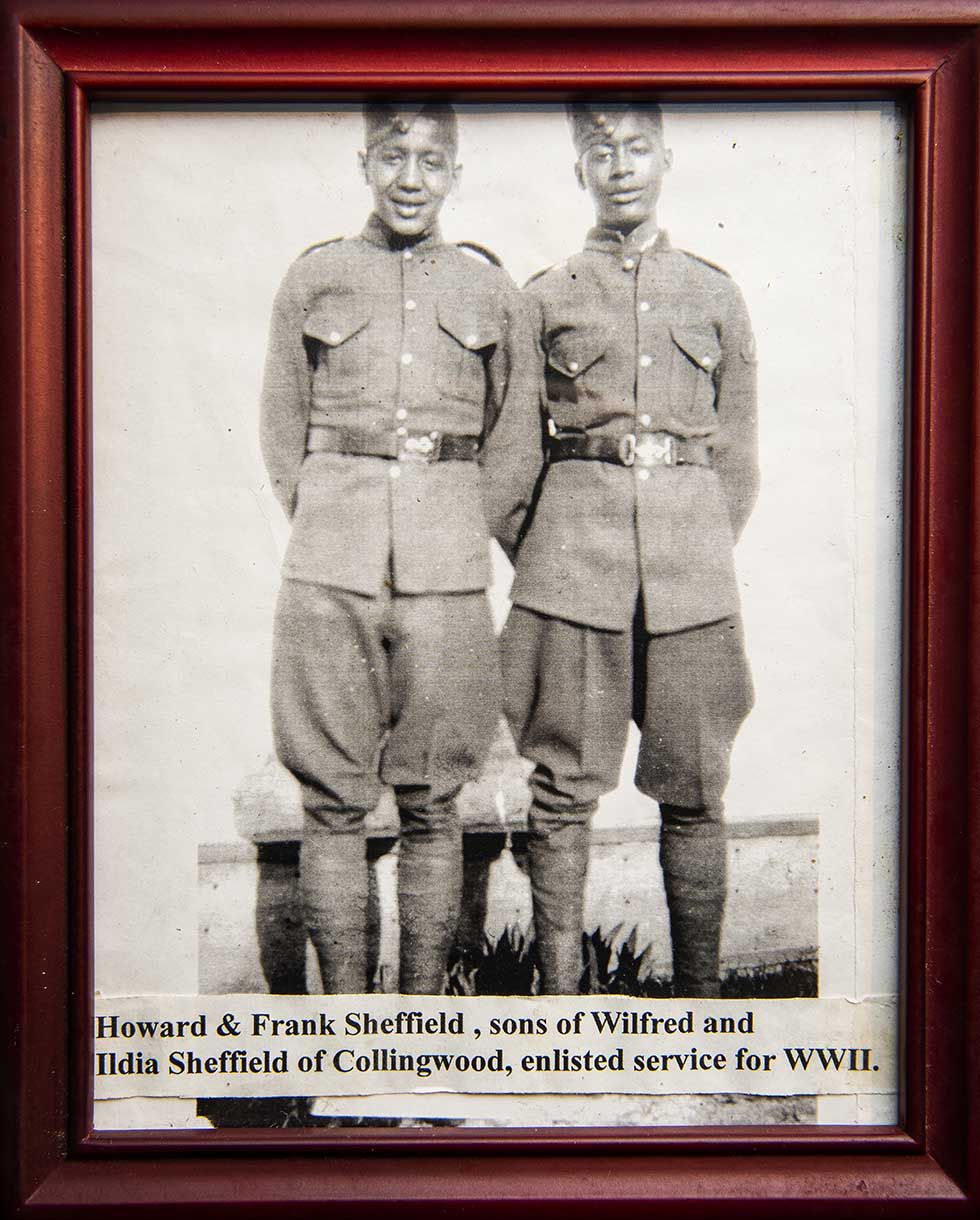

Carolynn and Sylvia’s grandparents, Ildia and Wilfred Sheffield, worked as cooks on several Great Lakes ships during the 1930s and 1940s. Later they established Sheffield’s Cedar Inn Restaurant in Collingwood. During segregation times, Black tourists travelling to the area would seek the safe accommodation available at Sheffield’s Cedar Inn. Several artifacts from their grandparent’s Inn are proudly on display in the museum. Nestled among trees, Sheffield Park features a contemplative “Heritage Walk” which recounts the story of Debra Sheffield. Debra died in 1854 at age 12 and is believed to have been buried in the Old Durham Road Pioneer Cemetery in Priceville. Also known as the Priceville Black Cemetery, this nineteenth century burial ground was plowed over in the twentieth century by a farmer. In 1989, a group of citizens led by Carolynn and Sylvia formed the Old Durham Road Black Pioneer Cemetery Committee and were granted permission to dig through a rock pile in the middle of a field. Four headstones, broken and discarded, were discovered, nearly lost to the mossy landscape. The names on the stones were confirmed as early Black settlers Christopher Simons, James Washington, and James Handy and his daughter Ellen (these last two are ancestors of Carolynn and Sylvia Wilson). The Committee secured an Ontario Trillium Foundation grant and erected a concrete pavilion to safeguard and memorialize the site. Debra Sheffield’s headstone, along with many others, is still missing.

The museum’s indoor holdings are spread throughout 16 refurbished buildings and the collection contains artifacts spanning many generations, including donations from “white families who grew up with the original homesteaders.” Inside the African Beginnings building, visitors are invited to move to the rhythmic sounds as they meander through the village where artisans display their talents, and the warriors hold their weapons. Walk past the kings and queens while you experience the vibrant marketplace. Further along, the Early Settlers’ display captures domestic life as families began claiming land—various tools and machines that were essential for building and farming are on display.

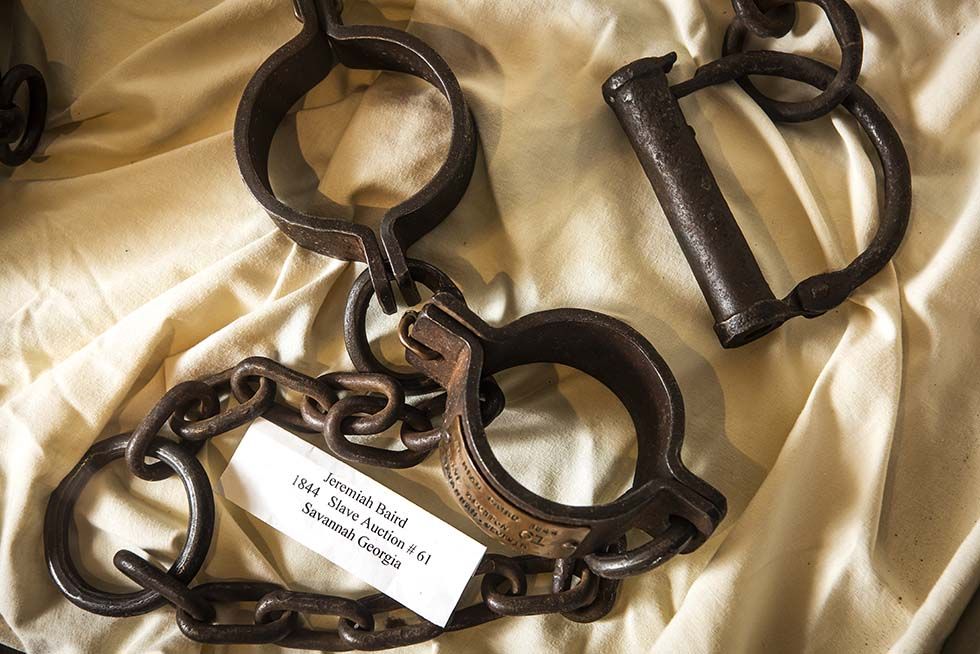

The later exhibits showcase a vast collection of Black dolls, postcards, and memorabilia, some of which conjure shock and horror at the abhorrent racism depicted. Racially-exaggerated illustrations and minstrel music-books, once created and circulated freely, are inescapably troubling. A collection of shackles and chains once worn by Black slaves lay solemnly in a glass encasement, while nearby is an assemblage of desks from the last segregated Canadian school (in Colchester, Ontario, which closed in 1961). These items serve as a shocking and powerful reminder of our bigoted history.

Sheffield Park tells the story of the Sheffield/Wilson family’s connection to Southern Georgian Bay while demonstrating how Black settlers constructively helped shape our industry and shorelines. The growing collection of heirlooms and culturally significant objects thoughtfully reshape how our shared history is told. Furthered by community support, Carolynn and Sylvia look forward to continuing to preserve the dream of their Uncle Howard Sheffield and invite you to visit the Sheffield Park Black History and Cultural Museum when they are able to reopen. “Howard Sheffield’s dream was to keep the events of the past visible so we, and future generations, would never forget. The dream continues…”

Follow Sheffield Park Black History & Cultural Museum on Facebook or visit them at sheffieldparkblackhistory.com