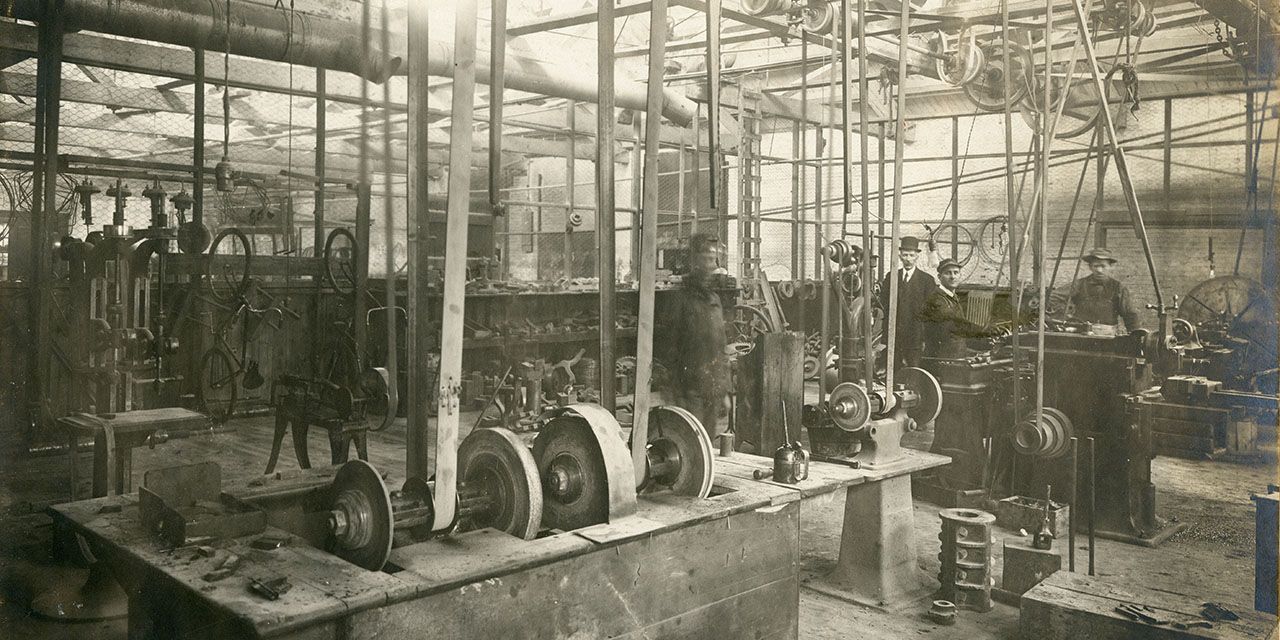

Interior of the Imperial Steel and Wire Co., May 1910. Four employees stand behind a series of belt systems.

The facility was destroyed by fire in 1919. Collingwood Museum Collection, X969.823.1.

The Bombers that Built Houses

Script by Ken Maher | Stories from Another Day, a Collingwood Museum Podcast.

Photos courtesy of the Collingwood Museum.

During the Second World War, Collingwood’s Clyde Aircraft plant helped build one of the fastest bombers in the sky—and in the process, laid the foundations for a neighbourhood that still stands today.

“IT says here that Russel is finally back from sick leave,” the man said from his seat at the dinner table. His wife, busy carrying food from the stove, gave an indistinct “hmm” in return. As her husband continued to rustle through the newsletter, the children began slapping each other under the table. “It also says that Norm had some tire trouble while on holiday, and that I need to ask Joe to tell me about a duck.” At that, even the boys looked up. Their dad gave them a wink and a shrug. “You know I don’t like you reading that at the table, dear,” his wife said as she laid out the roast. “Clyde Aircraft may help us pay for this lovely new house, but you don’t have to bring them to dinner. Hand it over.” The husband surrendered the company newsletter and ruffled the hair of his youngest. “Yes, ma’am,” he said with a mischievous smile. But she didn’t hear him, as she was herself lost in the pages. “Well, will you look at that—Farrel Ross’ sister was presented to the Queen,” she said, standing by her husband, paper still in hand. “Mom, no reading at the table!” came the cry from the children. “Boys, don’t disrespect your mother,” came the chuckled reply.

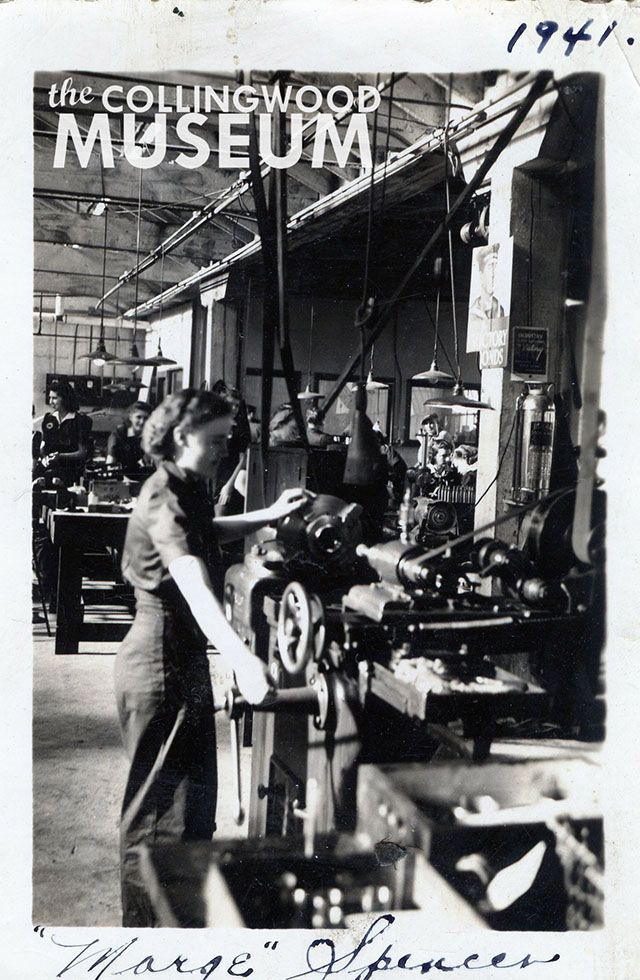

It is, or could be, a typical early summer evening in 1945. And the family is, or could be, any one of hundreds here in Collingwood who found work through the war in Collingwood’s secondbiggest employer—Clyde Aircraft Manufacturing. This landmark business opened in Collingwood during the Second World War, producing much-needed parts for the war effort. Clyde was a modern engineering and machine shop, including a toolmaking department, cafeteria, and fully equipped first-aid clinic supervised by a registered nurse. It was so large that it also published a regular newsletter for its employees and boasted both a men’s baseball team and a women’s softball team known respectively as… well, that’s a story for another day. On this day let’s stick with the business side of things. And this business was “an invaluable asset to our industrial side,” as a local paper raved.

Four Clyde employees pose in front of a tank displaying a sign promoting a softball game at Exhibition Park between Base Borden and the Clyde Aircraft Bombers. Collingwood Museum Collection, 005.25.1.

And an invaluable asset to Canada’s war effort too. While the Collingwood Shipyards was busy producing trawlers and corvettes on the other side of the harbour, Clyde Aircraft employed over 500 people to work in its 65,000-square-foot factory, where they were busy manufacturing a wide range of parts and materials for tanks, army and navy guns, and aircraft—including canopy tops, fuel oil, and hydraulic pipes. All of those aircraft parts (for which the company, of course, bore its name) were destined for the infamous Mosquito Bomber.

The de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito (nicknamed the “Wooden Wonder” or “Mossie”) was constructed mostly of wood. And while many at the time thought that was crazy, for this very reason it was one of the fastest operational aircraft in the world for most of the war period, with a top speed of 415 mph. That was over 100 mph faster than any fighter in the sky. Originally conceived as an unarmed fast bomber with a payload as large as the B-17, the Mosquito’s use evolved during the war into many roles, including low-to-medium altitude daytime tactical bomber, high-altitude night bomber, pathfinder, day or night fighter, fighter-bomber, intruder, maritime strike, and photo-reconnaissance aircraft. It was also used as a fast transport for high-value cargo to and from neutral countries through enemy-controlled airspace. The Mosquito could do everything—and very well.

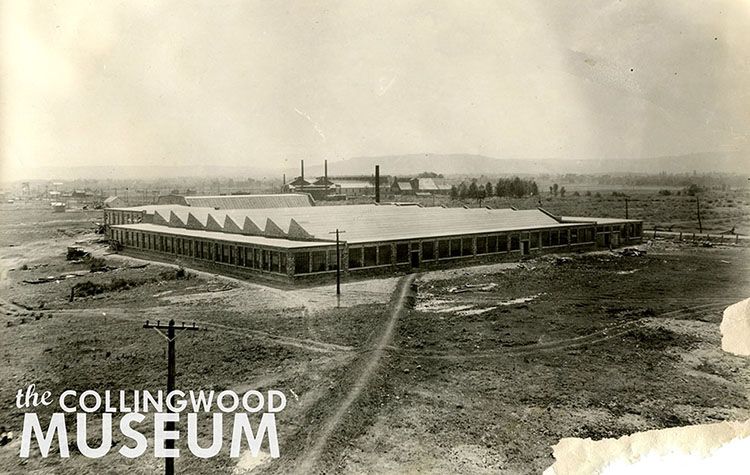

The Clyde Aircraft Manufacturing Company Limited on Balsam Street, 1941. Collingwood Museum Collection, X2010.47.1; Huron Institute No. 2825.

The Kaufman smokestack, the last part of the factory to be demolished in 2008, stood on the east side of Balsam Street. Photograph by Paul Young. Collingwood Museum Collection, 2018.8.5.16.

From Steelworks to Sofas

The site has had many uses through Collingwood’s history, both before and after Clyde Aircraft’s operation in the 1940s.

The Imperial Steel and Wire Co. operated on the Harbour Street site from 1904 until 1919 when the main building and adjacent structures were struck by a devastating fire. The fire was attributed to oil residue on the wood floors and spontaneous combustion. The factory was rebuilt between 1919 and 1921, and the plant enjoyed a short operation until 1925. The facility was later re-opened as the Huronia Wire Company after a lengthy closure. On August 15, 1940, an agreement was reached with Clyde Aircraft for the sale and purchase of the premises for use during the Second World War.

At the end of Second World War, Globe Plywoods Limited converted the Clyde Aircraft plant to build “knockdown” furniture for Great Britain. This style of ready-to-assemble furniture was easily shipped and required little storage space. When the company began operations, twenty percent of its workforce was composed of veterans. A.R. Kaufman of Kitchener provided capital for this new industry, and the rest is history.

Globe Plywoods Limited became Kaufman Furniture and remained an important Collingwood industry until its closure in 2005. In its early years, Kaufman produced lower-priced furniture. In the 1960s, its direction shifted to compete with American imports. A leather upholstery department was introduced, and furniture designs were upgraded for a higher price point. Both the factory and iconic smokestack were demolished in 2008. Today, the site remains vacant along Highway 26.

An interpretive panel along Balsam Street on the Collingwood Trails speaks to the history of the property.

Clockwise from left: Huron Institute No. 748. “Marge” Spencer at work inside the Clyde Aircraft facility, 1941. Collingwood Museum Collection, 003.89.2; Victory Village home of Grant Temple on Hurontario Street South in 1943. Collingwood Museum Collection, X970.929.1; Huron Institute No. 2880. The Imperial Wire and Steel Co. along Balsam Street in 1921. Collingwood Museum Collection, X972.43.1.

Ten different variations of that Mosquito Bomber were made right here in Canada. More than 1,000 planes by the end of the war (and even a couple after the war ended). It all happened at the Downsview Airfield with parts gathered from places like Collingwood.

Clyde Aircraft employed so many people that the resulting influx of workers created a housing boom, and the little part of our town that became Victory Village was born. It came to be through the efforts of the federal crown corporation Wartime Housing Limited. Through the early 1940s, 100 homes were slated for construction between Hurontario and Birch Streets on Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Streets. At the time of construction, the homes sold for anywhere between \$1,800 and \$2,300.

And here is where history turns an interesting full circle. After the war, the facility was retooled to make flat-pack bedroom suites under the name Globe Plywoods Limited. Not too long after that it was renamed Kaufman Furniture. Kaufman shipped its quality tables and chairs across North America and manufactured highend furniture for numerous North American hotel chains. How many of the homes built in part by Clyde Aircraft were also then furnished with the peacetime products of Globe and Kaufman?

The Kaufman factory closed in 2005 and was finally demolished in 2008, but Victory Village—the houses that the Mosquito Bomber built—are still here today. E