Postcard with a view of Chatsworth, ca. 1920. PF52S1F1I4, Grey Roots Archives.

MURDER, BIGAMY & NEW BEGINNINGS:

THE WICKLOWS OF CHATSWORTH

by Elysia DeLaurentis

Full of surprising twists and unexpected turns, the story of the Wicklow family leads from the dankest of prison cells to the office of the Prime Minister himself.

Some may recognize the names of Edward and Ellen Wicklow from rumours long-whispered by older generations. Their surname was at times spelled Wicklam and they lived in the Chatsworth area for years. Impoverished and illiterate Irish Famine refugees seldom left a deep mark in the historical record. The lives of the Wicklow family, however, were replete with tales of murder, bigamy and new beginnings.

It was around 1832 in Northern Ireland that Edward Wicklow and Eliza Loughead were born. Beginning in the late 1840s, a series of crop failures plagued the island leading to widespread starvation. Many chose to emigrate out of desperation. The Wicklow and Loughead families became two of thousands who, hoping for a better life, fled on crowded ships destined for the new world.

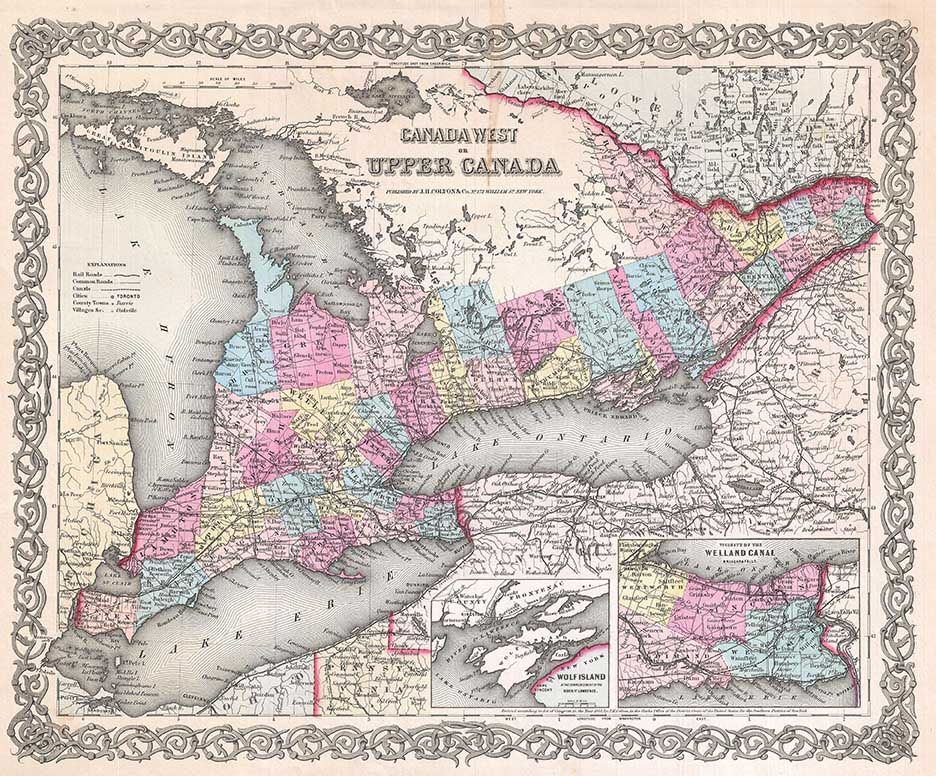

Both families settled in upper Garafraxa Township, northeast of Fergus. The population of the area had grown in the 1840s with the clearing of a new road to Georgian Bay. The Owen Sound Road, as it was known in Garafraxa, later became Highway 6. Wed in 1853, Edward and Eliza established a small inn and tavern in the township and started a family. As Edward succumbed to the tavern’s temptations, Eliza found him increasingly unpredictable. In 1859, he shocked the community by settling a dispute with a lodger by lashing out with fatal results. Edward was charged with murder and subsequently sentenced to be hanged.

Living with Edward was often difficult but Eliza was reluctant to be left in the woods to raise two children, clear the land and run a tavern alone. Though uneducated and from a low social class, she was strong-willed and determined. She mustered the courage to petition the Governor General, urging him to reconsider Edward’s sentence for her sake and that of her children. She had taken a wise tack, for Victorians understood the family unit as the very foundation of society. Three days before Edward was to be hanged, authorities commuted his sentence to life in prison.

Edward was soon transferred to the Kingston Penitentiary where he communicated with Eliza via letters. She may have complained about her workload, for he asked his brother to go check on her. William Wicklow then showed up at their tavern and made himself at home. Suddenly it was William giving the orders, reaping the profits and eating the provisions. Eliza later lamented that, “He robbed me of all I owned.” It was also during this period that she became pregnant with his child.

“Map of Canada West or Upper Canada,” published by J. H. Colton & Co. of New York, 1853.

The poor wife of a murderer trying to get by on her own was one thing, but living in sin with the murderer’s brother and producing his child was too brazen for the people of Garafraxa. One fateful night, they acted—a group of men lured William and Eliza out of the house and tied them up. They then went to work destroying the home and tavern. This was no simple warning to amend one’s ways; the community wanted the Wicklows gone.

Still calling the shots, William took Eliza and the children to the United States. Eliza later returned but, feeling unwelcome in Garafraxa, on Edward’s urging she moved to Portsmouth village, near Kingston. There she found work as a housekeeper for one of the prison guards. The connection would have allowed Edward and Eliza to keep in touch.

This was helpful because Edward needed Eliza to be his agent on the outside. If he blamed her for his brother’s actions, she may have agreed in order to redeem herself in Edward’s eyes. In late 1868, she sent a petition for her husband’s release to Sir Alexander Campbell. The following spring, she travelled to Ottawa to meet with Senator Campbell in person. During that trip he presented her to the Prime Minister. She impressed them both.

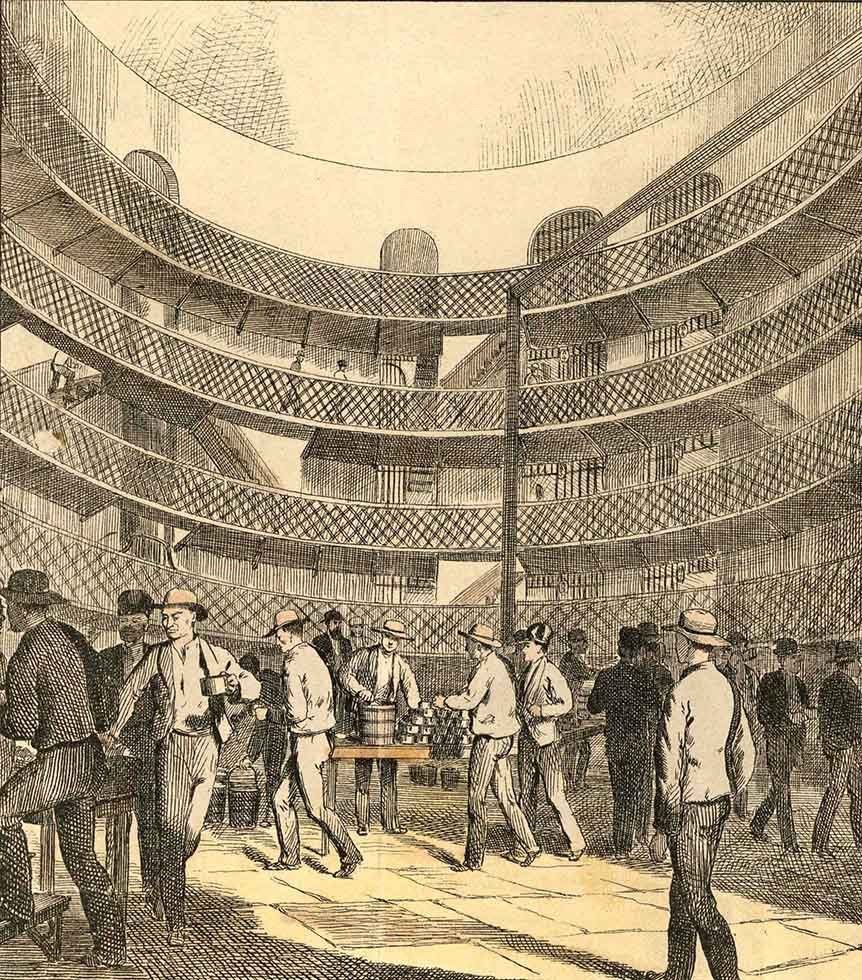

Yet by the end of 1869, Edward continued to languish in prison. He urged Eliza to go to Ottawa again but this time she refused. It had taken her two years to save the money needed to make the first trip. She didn’t have the means to do so again. Edward had, however, been doing his part and was considered a model prisoner. His conduct, coupled with Eliza’s efforts, proved effective and Sir John A. Macdonald granted Edward Wicklow a pardon for his crime in 1871.

According to prison records, Edward expressed that “kind treatment is best to improve a man.” It seems he was in no hurry to apply this same theory to women. He used his exit interview to disparage his wife, likely because Eliza had by then foresworn him. After learning that he’d portrayed her as consistently unfaithful in letters to friends and family, Eliza later explained that, “it so angered me after all I did for him that I never looked after him after he got out of prison.” In December of 1871, Edward Wicklow was on his own when he left the penitentiary.

Edward first traveled to Prescott where his daughter Ann was living. There, he threatened her with death unless she signed a paper falsely attesting that Eliza was deceased. Edward was by then a hardened criminal who had proven himself capable of murder. Ann signed the document.

Edward then headed west where he arranged to give a public lecture in Fergus about his life and imprisonment. Newspapers haven’t survived to provide the highlights but it’s not hard to do some surmising. He charged no admission to ensure a large attendance, likely seeking to repair relations in his former community and to do this at his wife’s expense.

Eliza’s efforts had been key to his release but Edward seems to have felt shame around her pregnancy during his incarceration, and angered by her subsequent abandonment. Painting Eliza in a bad light became how he explained her absence as well as his heavy drinking that caused such tragedy. It also may have been a way to publicly excuse himself from the marriage, for by then, Edward had lined up Eliza’s replacement.

Male prisoners in the dome of the Kingston Penitentiary, as published by the Canadian Illustrated News in 1875.

That there was another woman is astonishing given that Edward had spent the previous twelve years locked up with men. More surprising is who that woman was. Ellen Dundas was none other than Eliza Wicklow’s good friend. Ellen had gone to Ottawa with Eliza, and may have also accompanied her on visits to the prison.

Ellen’s life was not without its own challenges. Also, from Northern Ireland, she had come to Canada as a teen during the Famine, settling in Toronto. By 1861, she was working as a servant in a Toronto hotel. She was still single four years later when she had a baby girl. By 1871, both had joined the household of Ellen’s widowed mother and brother James, who farmed in Grey County.

…a group of men lured William and Eliza out of the house and tied them up. They then went to work destroying the home and tavern. This was no simple warning to amend one’s ways; the community wanted the Wicklows gone.

Edward Wicklow and Ellen Dundas must have kept in touch for they married in Toronto a few months after his release. For both, it was a new beginning. A single mother in her early forties, the marriage offered Ellen legitimacy and a household of her own. Spurned by Eliza, it provided Edward a companion to keep house. The new family found some land in Sullivan Township, not far from the Dundas family farm, and soon after welcomed Edward Jr.

While Edward and Ellen were establishing themselves as farmers near Chatsworth, Eliza was seething. Alone and facing financial difficulties, she had also become a woman scorned. Eliza was outraged at the audacity and betrayal of those who should have had her best interests at heart.

Eliza was however resilient however, and by 1876, was running a boarding house in Toronto. She had been successful working government systems to her advantage, by appealing to the men who controlled them. She planned to do so again. That May, she made her way to the Toronto police station and laid a complaint: her husband had committed bigamy.

Detectives then boarded a train for Chatsworth, apprehended Edward Wicklow and brought him back to Toronto. His case was first heard by the Magistrates’ Court. The minister who had married Edward and Ellen in 1872, and those who stood up for them, were each called on to recall the ceremony. To establish evidence of the first marriage, the court also heard from Thomas Black, who’d been Edward’s best man when he’d married Eliza, as well as her sister, who’d served as the maid of honour.

Then Edward had his say, handing a statement to the magistrate to read before the court. It was dealing with his wretched wife, he explained, that drove him to the bottle, resulting in the unfortunate death of his lodger. Edward accused Eliza of taking the opportunity of his imprisonment to revel in adultery, even bearing another man’s child. Because of this, he falsely claimed, authorities had forbidden him from reuniting with her after his release.

The magistrate was appalled. He decried Eliza “a bad woman” and chose not to call her as a witness. Despite this, the jury found that Edward Wicklow had wed Ellen Dundas while still married to Eliza. His case would proceed to the Assize Courts.

The Dundas family stone stands prominently in St. Paul’s Anglican Cemetery north of Chatsworth. To the right of it in the same row is the grave marker of Edward Wicklam [sic, Wicklow]. Photo by Elysia DeLaurentis.

Though technically a ‘win,’ Eliza was beyond indignant at her treatment. Her anger at the struggles and injustices she’d faced came through clearly in the statement she submitted by way of a reply. In it, she recounted events as she knew them to be true (which historical evidence corroborates). She swore that Edward’s statement was false, directing incredulity towards the magistrate for pronouncing her a “bad woman” on the word of “a discharged convict, and since his discharge, a bigamist.”

That October when Edward returned to Toronto to face the Assize Courts, Thomas Black was not in attendance. Eliza Wicklow was also absent. Without two key witnesses to the first marriage, the case was discharged. Edward had avoided another prison sentence and discredited his first wife, all while getting to return to the second.

For years, Edward and his second family farmed in Sullivan before moving into Chatsworth proper. There, he found work as a stone mason, employing skills that he’d learned in prison. Little has otherwise been recorded of his life in Chatsworth. A poor man when he died in 1887, Edward demonstrated care for his second family by having taken out life insurance. To his further credit, they erected an enduring stone to mark his grave in St. Paul’s Anglican Cemetery.

After Edward’s death, Ellen found a place to live at the southern end of the village where she opened a grocery store. The community’s acceptance of the family was demonstrated by its support of Ellen’s business which remained a fixture in Chatsworth until her death in 1915. Buried next to her husband, the simple text on her tombstone belies the tangled complexities of her earlier life and that of the man she married.

As for Eliza Wicklow, her final years have been lost to time but she was an extraordinary woman. Despite her lowly status and lack of education, she stood up against injustice, petitioned the province’s most influential men, and consistently showed resilience and determination in the face of adversity. With time, Eliza may have overcome the challenges of Edward’s actions to find her own new beginning.

Elysia DeLaurentis is a local historian based in Elora. Through her business, Oakenwood Research, she tells the unique stories of Ontario’s people, places and events. This article sprang from a 2023 presentation for the Grey Roots Spring Lecture Series. Elysia hopes to explore the Wicklows’ lives more fully in a future book. E

Elysia DeLaurentis is an Elora-based historian and owner of Oakenwood Research. The information in this editorial originated from her 2023 presentation at the Grey Roots Spring Lecture Series.