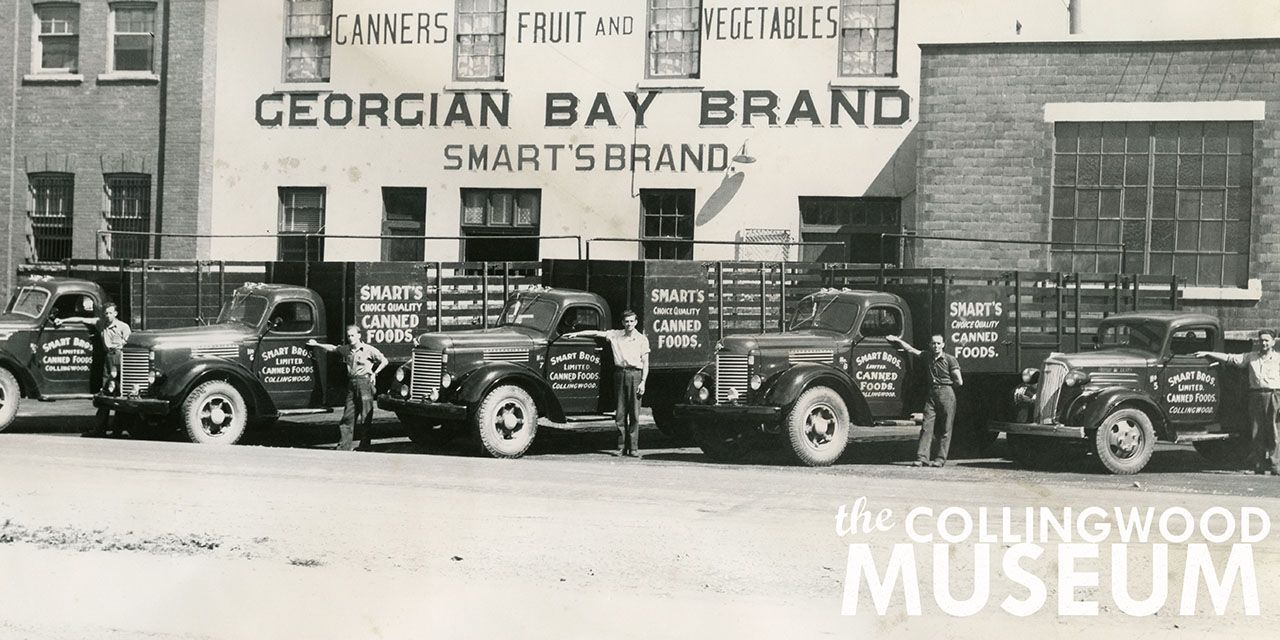

Smart Bros. delivery drivers outside the bustling First Street cannery, 1949. Collingwood Museum Collection, 994.33.9.

Driving Change

Script by Ken Maher | Stories from Another Day, a Collingwood Museum Podcast. Photos courtesy of the Collingwood Museum.

In the heart of wartime Collingwood, a young woman’s unexpected job interview marked the start of a remarkable journey—for her, and for the legacy of the Smart Brothers, whose pioneering spirit and community roots shaped the town for generations.

“Good morning, Miss Kelly?” Startled, the young woman hastily put her compact mirror back into her purse. She wouldn’t have time for a final glance before going in—her interviewer, it seemed, had come out to meet her. The well-dressed man wore a sharp suit and a big smile. As he extended his hand, he said, “I’m John Smart. Welcome.”

Eleanor took his offered hand and was about to thank him for the opportunity to apply for a job. Like many young women, she had left her home in Mulmur to find work here in Collingwood. She had heard that Smart’s Cannery was always hiring. But before she could even begin, the man before her asked a question: “Do you have your driver’s licence?” The whole thing being so surreal, Eleanor responded by instinct. “Why?” she asked in turn. “Do I need one to walk through this place?” With a big laugh and a smile, Mr. Smart told her they were looking for a woman to become their first delivery driver for their flower business—and he thought she might just be the one they had been looking for. The truth was, Eleanor had not in fact driven before this, but she jumped at the opportunity. Women delivery drivers were so rare as to be almost unheard of.

In short order she was fitted for a Smart’s green uniform, complete with jacket and cap, and shown to her new truck with the Smart’s logo crisply painted on the side. And in no time at all, as her deliveries took her to all corners of the area, Miss Kelly (later known as Mrs. Eleanor Sproule) would be instantly recognized and well-loved by all the people she would meet each day. And as she herself would later say, “It sure beat standing up to your elbows in tomatoes!” (Enterprise-Bulletin, Nov. 14, 2008).

This life-changing day for young Eleanor took place in 1942, in the height of wartime when most able-bodied men were away on overseas service. Eleanor’s popularity with the customers—not just because of the novelty, but also because of her congeniality and exemplary service—would go on to open other driver jobs for women in Collingwood. But her daily deliveries would also serve as a visible reminder of the community-minded hiring practices of a local business. A business that was a pillar of Collingwood for 80 years. A business that routinely went out on a limb to employ, what seemed like, at least one member of nearly every Collingwood family at some point or other… men, women, even students and children.

Smart Bros. Cannery employees—mostly women—pose on First Street, c.1950. Collingwood Museum Collection, 008.15.1.

And it all began with a man named John Smart, who emigrated to Canada from Dorsetshire, England, in 1846. Eventually John and his wife Isabella would find their way up to Collingwood on the recently completed railway. He worked as a conductor for the Northern Railway until poor health caused him to retire. So, what does one do when they find themselves too sick to work anymore? Why, buy a farm, of course, and begin a market garden!

In 1890, John purchased seven acres of land on Campbell Street, which at the time was considered to be way out in the country. In short order he added another five acres across the street. This would set a pattern for the great success he would see over the coming years.

At first John would be helped by one of his sons, Norman, and after a couple of years another son, George (who went by W.G.), came on board and the father was finally able to retire. Together, Norman and W.G. decided to call the business Smart Brothers Limited. Eventually, two of W.G.’s sons, John and Edward, would continue on the “brother” part of the Smart Brothers operations.

From seven to 12 to 60 acres in short order. Within twenty years, Smart Brothers had acquired 200 acres of land with sections for fruit, vegetables, and flowers. At their peak they would own around 500 acres of local farmland. The operation became so expansive that manure had to be imported from Toronto to help fertilize all their fields—cherries, plums, apples, tomatoes, strawberries, raspberries, asparagus, onions, beets, carrots, lettuce, radishes, cabbage, parsnips, cucumbers, corn, and celery. Many were quick to tell them there would be no demand for their crops. They firmly believed that if they could grow it, a market would be there. And they were right.

In those early days, Collingwood was a busy port so most of the produce was shipped out five times a week in season by packet steamer to all parts of the North Shore of Georgian Bay. Sauerkraut and cabbage were the most popular at the time. As Tracy Marsh recorded in the Enterprise-Bulletin, in a brisk business cabbage went for $2.25 for a 150 lb. crate. The rest went into making some 20,000 cases of sauerkraut a year. The demand was so large that the sauerkraut was fermented in vats six to eight feet across and ten feet deep.

Smart’s employees sit on a horse-drawn wagon filled with pumpkins along First Street. Behind them: the three-storey Mountain View Hotel (formerly the Globe Hotel) and the peak of the Shipyards’ Machine Shop.

Part of Smart Brothers’ success was their continued innovation and never-ending search for opportunities. W.G. took special care to reclaim much of this area’s swampland. He turned it into productive fields through expert tile drainage, all of which he did by hand. He was seen, even into his 80s, showing others how to continue the important work. His son John was a noted chemist, particularly ahead of the curve in understanding the need for trace elements and soil amendments to get the best growth. While he was not officially a student, he did spend much time studying chemistry at the Ontario College of Agriculture in Guelph.

Knowing that bees were vital to their many crops, Smart Brothers took up beekeeping and sold honey on the side. Seeing that birds were very effective at keeping down the insect problem, they built houses to encourage purple martins to come back year after year. Not wanting their many greenhouses to be empty in between vegetable seasons, they took to planting flowers between other crops. This in turn opened up further opportunities, as Christine Cowley records in her book Butchers, Bakers, and Building the Lakers: at Christmas, Easter, and on Mother’s Day, Henry Smart (a brother to Norman and W.G., who ran a very successful tailor shop here in town) would pack up his suit samples and sell seasonal flowers from the farm. Over time this would turn into a full-blown flower shop in the same spot.

Edward Smart introduced a dietetic line of products and under his leadership Smart Brothers was the first company in Canada to provide a calorie-reduced line of canned products. This was no small feat considering their very popular line of jams contained three times as much sugar as fruit!

As early as 1911, Smart Brothers set up their very own canning factory on the farm, generating 70,000 cases of produce annually. In those early years every single can had to be hand soldered. It wouldn’t be until 1927 (and in the new canning factory) that a can closing machine would finally be added. Eventually the shipping of fresh produce on the lake-bound boats was replaced by the shipping of canned goods in a fleet of trucks.

The brand-new canning factory, built on the north side of First Street in 1925, would be large enough to produce some 325,000 cases of product a year. In its heyday, this canning factory had a record 331 employees with another 150 working on the farmlands. To service the growing fleet of trucks and equipment, a garage and machine shop was built across the street from the canning factory. There were twelve more employees working there and in the Floral Division (like Eleanor Kelly).

The rooftop of Smart’s cannery offered a prime view of Collingwood Shipyard launches. On August 4, 1949, crowds gathered to watch the launch of Hochelaga—then the largest ship ever built in Canada. Collingwood Museum Collection, 2019.4.1.2.

Smart Brothers canned goods were shipped from coast to coast, and later even as far away as West Germany and Great Britain. The trucks drove from Collingwood to Montreal two times a week. Canned goods went down and loads of sugar came back home. At the height of their production, Smart Brothers had over 120 different products they sold worldwide.

It is little wonder, then, that at one time they were Ontario’s largest fruit and vegetable farming operation. Especially during the Depression-era, Smart Brothers was the single largest employer in Collingwood with wages that often equalled those in the shipyard. In fact, during the Depression the shipyard would lay dormant for significant periods. Yet even in those lean times, Smart Brothers still hired hundreds of employees. Not only did they hire men, women, students, and even local children, many local farmers sold produce to them. During harvest season, local farmers would bring tractors and trailers and they would be lined up all the way down Pine Street as they waited to be weighed and inspected at the canning factory, turning today’s fresh produce into tomorrow’s canned goods. “Packed at Flavour Peak,” as the Smart Brothers logo said.

But beyond simply providing work for so many in the area, Smart Brothers gave back to the community in so many other ways. The roof of the cannery was the place to watch the launch of the ships. And employees were always welcome to take a break and invite their families to the spectacle. As the business continued to buy up farmland, they also acquired a number of houses that went with them. These they turned into homes for their workers to live in.

At Christmas time, everyone at the factory received a free turkey. Donald Hurst recounted in a 1994 interview with the museum, and recorded in the local history files of the Collingwood Public Library, that dented and unlabeled cans were sold to the employees at a very significant discount. Sometimes this led to some funny stories in the Hurst’s kitchen, but it was a godsend, especially in the lean years of the Depression. Frank Simonato, in a similar interview, tells of how George Smart (W.G.) was always well-known for his kindness to employees. He once gave out a personal loan for one to buy a house, allowing it to be paid back out of the employee’s wages. Another time it is said W.G. paid five years’ worth of taxes for another man who was severely injured while serving as a firefighter. He was a devoted supporter of our hospital here in Collingwood, supplying the funding for much of the X-ray equipment used for many years. As well, Smart Brothers trucks were allowed to do hauling jobs for many local groups like the Boy Scouts. David Christie, in a further interview, recalls how John Smart served as chair of the Hospital Board. John was also instrumental in getting the Collingwood Ski Club started.

Now home to Campbell Lofts, the building at 238 Campbell Street once housed Smart’s head office, packing house, and cold storage.

W.G.’s house was located on the Campbell Street farm and continues to stand at 234 Campbell Street today, just east of the Campbell Lofts.

And the care the Smart’s business showed for this community and its people went even deeper still, for all their equipment was purchased locally whenever it could be. Their work uniforms were made by locals. All the painting, logo work, and auto body repairs for their fleet of trucks was sent to local businesses. Businesses like Dey’s Autobody, which first opened shop in 1871—not to service cars, but as a… well, that is a story for another day.

On this day, we are recalling the story of Smart Brothers, and all they did for our town. And sadly, just like the story of the Telfer Brothers Biscuit Company we covered in the very first episode of Season 3, this 80-year-old company would also end in a sudden and unexpected way. In 1964, after a number of family deaths left Edward the sole Smart brother left to run the company, Canada Vinegars purchased the business with the goal of expanding it even further. Now at this point, Edward had already turned down an offer from them earlier. But with the promise of doing even more for the people of Collingwood under the new business model, a deal was finally made. However, what no one knew at the time was that Canada Vinegars’ mother company in England ran into financial difficulties. Difficulties that led them to dissolve all foreign assets, leading to the sudden and surprising closing of Smart Brothers. By 1970 they were simply gone. Sold off for scrap and pieces, and no one here in town could say or do anything about it.

But gone does not mean forgotten, and if you know where to look, you can still see the legacy of Smart Brothers all over our town, even 55 years later. Some years ago, a boiler for the old greenhouses was found lying in a field near a newly built subdivision just east of High Street. It was set up along the waterfront trails with a marker detailing Smart Brothers’ history. You can see them for yourself today right between the Labyrinth and our town’s Arboretum at the north end of Hickory Street.

The farm’s old apple storage building is now part of Campbell Lofts at 238 Campbell Street (formerly Smart’s Apartments), full of unique reminders of its long history. The Collingwood Nursing Home is on the approximate spot where the old greenhouses once stood. The building across the street on the corner of Campbell and High Streets, which now houses a number of community charities, first served as the Smart’s winter rhubarb house. The second canning factory stood where the LCBO now stands today. And the garage and machine shop was right where Loblaws now resides.

But above and beyond all these are reminders of the many lives that were touched by Smart Brothers. Youngsters who had their first jobs after school or over the summer, and the men and women who were given a chance to make a good living in the same town they grew up in. People who learned the value of hard work and giving back to the community that you live in. The very same people who have continued to do so even to this day. E