The River is Calling and I Must Go

By Cara Williams | Photography by Clay Dolan

Retrace the footsteps of renowned naturalist John Muir on Meaford’s Trout Hollow Trail— where beauty and history meet a little-known chapter in the life of one of the world’s greatest conservationists.

As I step onto the leaf-dappled path at Trout Hollow in Meaford, the morning air is thick with birdsong and the earthy scent of early summer. This trail, winding gently through the woods along the Bighead River, is more than just a scenic hike. It’s a passage through time—into a lesser-known chapter of John Muir’s life, long before he became a leading voice for wilderness preservation.

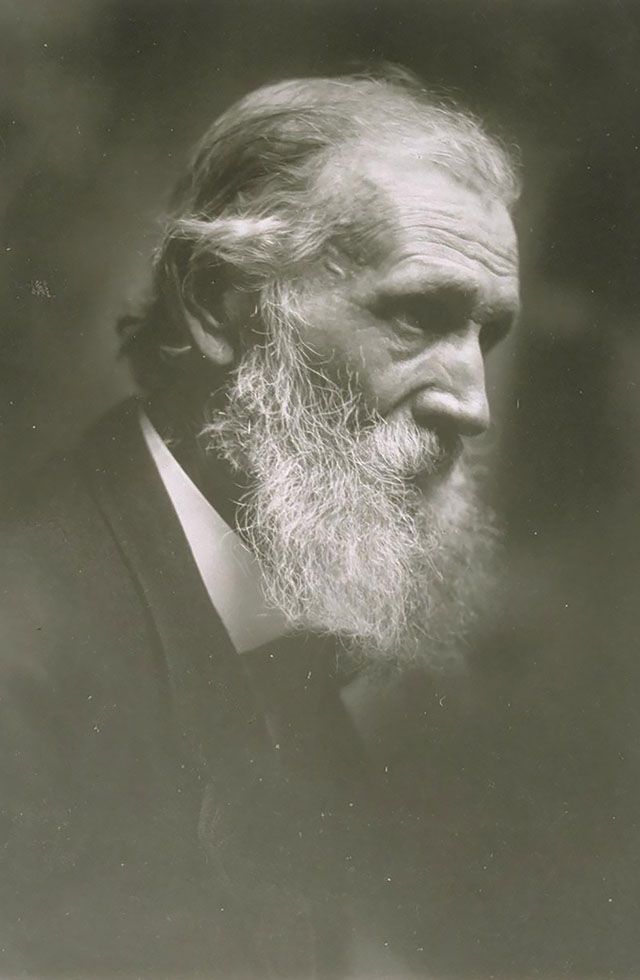

Most people know Muir as the Scottish-born American naturalist who championed the wild landscapes of the western United States. He founded the Sierra Club in 1892, inspired the creation of Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks, and famously wrote, “The mountains are calling and I must go.” But did you know he once lived in this quiet corner of Ontario?

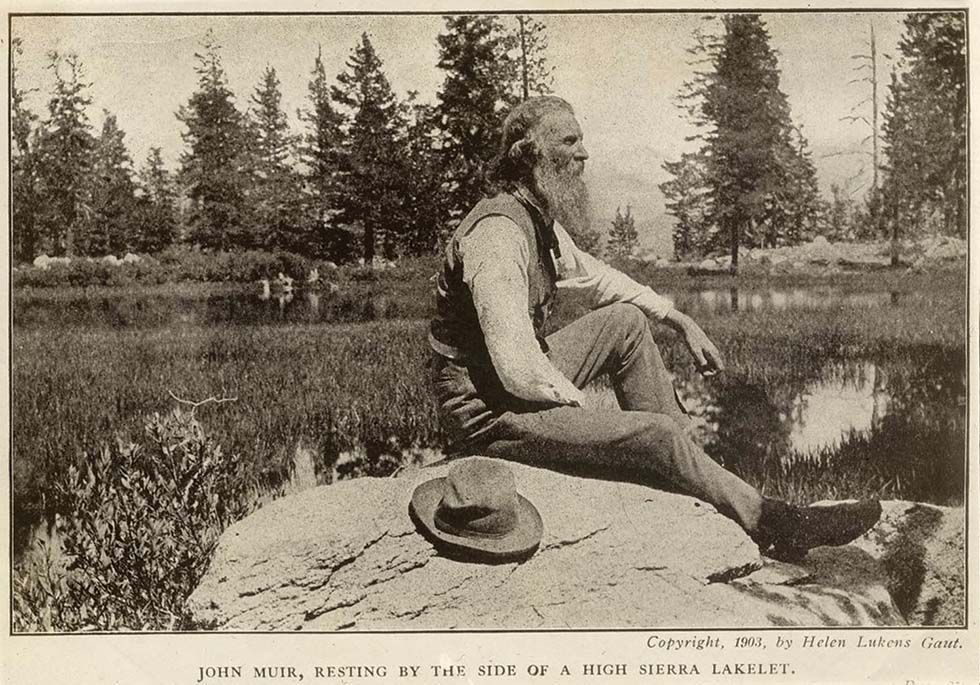

Born on April 21, 1838, in Dunbar, Scotland, John Muir immigrated to the United States with his family in 1849. In 1864, fresh from university and in his mid-twenties, he travelled north and spent nearly two years in Meaford. Those years would prove pivotal—shaping the ecological curiosity that would later define his legacy.

John Muir, beside a High Sierra lakelet, 1903. Photo by Helen Lukens Gaut. Public Domain.

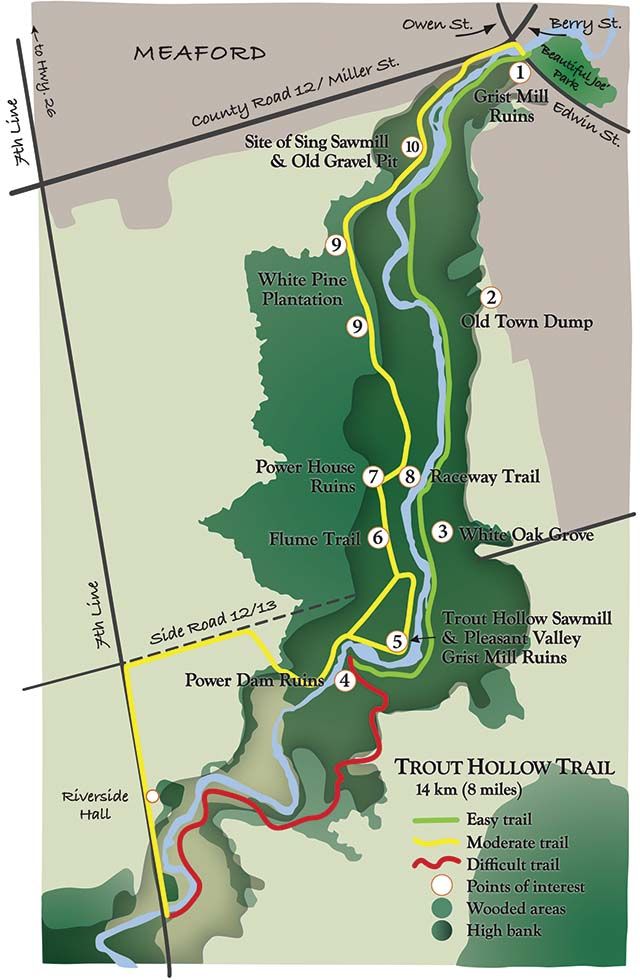

The Trout Hollow Trail is a 15-kilometre walking loop that traces both sides of the Bighead River. A moderate hike, it meanders through mature forest, over wooden footbridges, and past limestone outcroppings and ruins. Built by Grey Sauble Conservation in partnership with private landowners and officially opened in 2002, the trail follows historic routes likely used by generations of locals. The full loop is composed of 7.5 km on each side of the river, but you don’t need to complete the entire circuit. Several shorter out-and-back options still deliver a rewarding mix of scenery and story. The trail is well-marked and gently undulating, with a few rocky or rooty sections but nothing too technical. It’s ideal for intermediate hikers, families, and leashed dogs with a bit of stamina. If you’re lucky, you might spot salmon, trout, deer, wild turkeys—or even a great blue heron wading along the bank.

As you follow the west side of the river, interpretive signposts guide you through the natural and cultural history of the site. Here, the trail tells the story of brothers William and David Trout—enterprising millwrights and early settlers who operated the sawmill where John Muir briefly worked in 1864 as a mechanical assistant and craftsman. Muir lodged nearby in a modest cabin and spent his free hours wandering the woods, sketching wildflowers and experimenting with plant presses. The Trout family name—fittingly, or perhaps with a touch of irony—still echoes in the area, as trout and salmon continue to run the same banks once shaped by industry. Remarkably, some Trout descendants still live nearby and have helped preserve this landscape and its story.

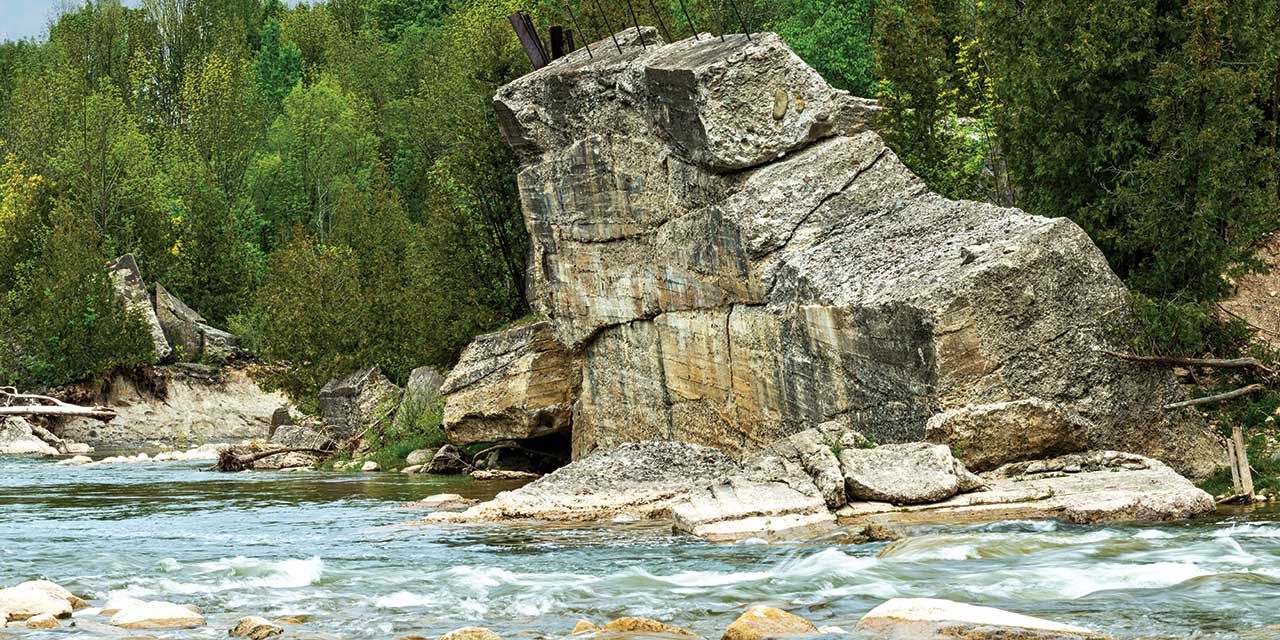

Much of that industry remains—its bones softened by time and overgrowth. The trail passes through the former site of the Georgian Bay Milling and Power Company, where remnants of stone foundations, sluice gates, and sections of the old S pipe still peek through the underbrush. Not far from here is the approximate location of the original Trout sawmill. Though little remains beyond moss-covered stonework and the steady ripple of the Bighead River, the site pulses with history. Parts of the trail trace the upper banks of century-old hydro and milling channels, now lined with cedar groves, trilliums, and columbine. It’s easy to see how Muir found inspiration here.

Around the two-kilometre mark, I pause beside the river, where the sawmill once stood. A few rough stones are all that remain, but in the quiet hum of the forest, it’s easy to imagine the clang of iron, the creak of timber—and John, sleeves rolled, immersed in both physical work and the awe of his surroundings.

He would later write: “I set off on the first of my long lonely excursions, botanising in glorious freedom around the Great Lakes and wandering through innumerable tamarac and arbor-vitae swamps, and forests of maple, basswood, ash, elm, balsam, fir, pine, spruce, hemlock… glorying in the fresh cool beauty and charm of the bog and meadow heathworts, grasses, carices, ferns, mosses, liverworts displayed in boundless profusion.” —John Muir, The Life and Letters of John Muir (1924)

The crumbling dam structure hints at the once-busy milling operations that shaped this quiet bend of the Bighead River.

That happiness was short-lived. In 1866, the Trout sawmill burned to the ground, taking Muir’s tools and belongings with it. With no means of livelihood, he returned to the U.S.—but his time in Southern Ontario left a mark. He had experienced the quiet power of wild spaces, and his writing suggests that those months helped deepen his ecological awareness. In many ways, the seeds of his later activism were sown here.

One of the beautiful things about Trout Hollow is its pace. This isn’t a race to a summit or a sprint to a view. It invites dawdling, observation, and thought—just as John would have preferred. The trail isn’t overly strenuous, but sturdy footwear is essential, especially after rain when the path can be muddy. There’s parking near the trailhead at the end of Edwin Street. While there are no washroom facilities, the route is well maintained thanks to local volunteers, Grey Sauble Conservation, and the Canadian Friends of John Muir. The latter group works to protect the trail and raise awareness of Muir’s time in these parts.

Come to the woods, for here is rest. There is no repose like that of the green deep woods. Here grow the wallflower and the violet. The squirrel will come and sit upon your knee, the logcock will wake you in the morning. Sleep in forgetfulness of all ill.”

—John Muir, John of the Mountains: The Unpublished Journals of John Muir (1938), p. 235. ©1984 Muir-Hanna Trust.

Near the turnaround point, I sit on a fallen log and unscrew my thermos, toasting John with a sip of strong coffee. What would he make of today’s world—a world where wilderness has become a rarity instead of a given? Would he be disheartened, or would he summon that same fierce optimism that lights up his essays? Either way, walking this path in his footsteps feels like a quiet tribute.

On the return leg, afternoon light filters through the trees, casting golden rays across the forest floor and setting the river aglow. A pair of hikers pass, chatting softly, with a dog trailing behind, tail wagging.

Remnants of Trout Hollow’s industrial past still line the trail: moss-covered stonework, foundations from the Georgian Bay Milling and Power Company, and rusted sections of the original S pipe, now slowly reclaimed by the forest.

John Muir once said, “In every walk with nature one receives far more than he seeks.” I believe he was right. I came looking for history, for a glimpse into his early days. But I left with a steadier heartbeat, a fuller sense of presence, and a deep gratitude for quiet places like Trout Hollow.

If you’re seeking a hike that offers gentle exercise, meaningful reflection, and a brush with the legacy of one of the world’s great nature lovers, Trout Hollow Trail is well worth the visit. Just bring your curiosity, your walking shoes, and maybe a notebook. After all, John would have brought his. E