Planting Seeds of Change

By Aidan Ware, Director and Chief Curator, Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Photography by Sara Angelucci

There is a portentous Cree proverb that states: “Only when the last tree has died and the last river been poisoned and the last fish been caught, will we realize that we cannot eat our money.”

Did you know that not only are there are some 20,000 species of wild bees that pollinate plants, but also moths, flies, wasps, beetles, and butterflies as well as animals such as bats, rodents, birds, and tree squirrels? Or that nearly 90% of flowering plants in the world are dependent on pollination? Doubtless, one seldom thinks about this as we peruse the bountiful and bright produce displays at the grocery stores, skimming along the polished aisles of gleaming fruit and misted vegetables, vaguely wondering why the broccoli is suddenly being shrink-wrapped. Somewhere along the lines, humans have become perilously disconnected from the land, from the source of our survival, from our mother earth – and we have come to a place where we take it for granted that these shiny, waxed and packaged grocery displays will always be stocked in readiness for us to pick and choose from. Yet literally everything, our entire food supply, relies on a fragile balance of pollinators. Without them, the glossy aisles are empty, our shopping carts are parked, and we have no way to feed ourselves.

Bees and many other pollinators are under threat with present extinction rates exceeding a thousand times higher than the past due to human impacts. We know through science that insects will make up the bulk of our future biodiversity loss, with 40 percent of invertebrate pollinator species (particularly bees and butterflies) facing imminent extinction. Changes in land use and landscape structure, intensive agricultural practices, monocultures, and use of pesticides have caused devastating fragmentation and degradation of pollinator habitats, leading to large-scale losses. Pests and diseases ravaging pollinator species have resulted from intense globalization and colonization. Climate change has caused higher temperatures, droughts, floods, and other extreme events that are essentially desynchronizing blooming times with the pollinators—all of this resulting in profound losses and threatening our global food security and indeed our future survival.

We cannot eat our money.

In her powerful book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer states, “To love a place is not enough. We must find ways to heal it.” So, although we are faced with monumental environmental changes and crises, there is hope that we can find ways to commit acts of restitution, to “restore honour to the way we live.” It’s about holding ourselves accountable for what we can do now and for the future.

The concept of change is always daunting, but taking small steps can often lead to larger leaps. As an institution, the Tom Thomson Art Gallery has made the environment one of the key curatorial priorities over the past two years and recently had the opportunity to work with the OPEN Team on a pollinator corridor project in Owen Sound. The OPEN Team is an innovative local partnership comprised of the Owen Sound and North Grey Union Public Library, the Billy Bishop Museum, the Community Waterfront Heritage Centre, and the Tom Thomson Art Gallery. In 2022, these organizations came together and launched a free joint membership for the public that spans all four institutions and in so doing, quickly discovered that when working together, the group was able to accomplish more complex projects, reach more people, and build critical cultural bridges that make the community stronger. From out of this organic cross-pollination of people and institutions, came the OPEN Team—a gathering of leaders who are committed to working with the community to steward and explore new ideas that have significant impact and resonance on and within current issues.

It was following the launch of the OPEN Card Membership, that environmental activist and poet Liz Zetlin approached the OPEN Team about her concept of a pollinator corridor in Owen Sound and from that time forward, the Team has been both committed to raising awareness about the connection between native plants and pollinators, and to helping launch the concept in the community through the development of planting projects at each institution set to take place in spring/summer 2023. A pollinator corridor is essentially a pesticide-free pathway consisting of native plants that provide the habitat and nutrition for pollinating species that allows them to travel across regions. Native plants are those that are indigenous to a land area – typically those that have evolved naturally and existed for many years in a region and they span everything from trees to flowers to grasses. Ontario has a long list of plants that are non-native and highly invasive, brought here through colonization. Some of these species are highly recognizable and include common buckthorn, dog-strangling vine (which you will no doubt endlessly struggle with in your garden), garlic mustard, and giant hogweed, to name just a few. The introduction of these plants to North America has greatly influenced the available habitat for pollinator species by making it much more difficult for them to travel distances as these plants do not provide food or shelter to the pollinators. Recognizing that pollinators rely on native plants to survive; a pollinator corridor provides a way that we can all work together to create a safe pathway for them to succeed. Ultimately the goal for the project isn’t to dig up all our hostas and toss them into the compost, it’s to educate people and inspire them to conscientiously build native plants into their existing gardens. It’s one small step but it’s an important way that we can work together as a community to create safe passage for these vital species and begin to positively reposition our relationship with the environment.

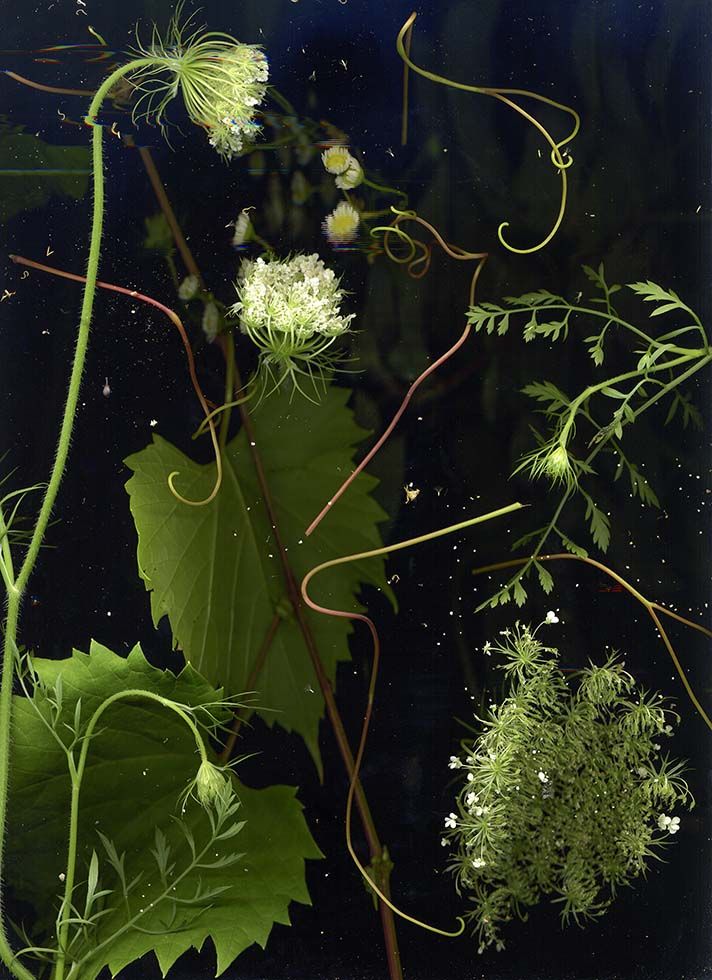

Heading into summer, the Tom Thomson Art Gallery will be exploring the impacts of settler colonialism on ecology through a major exhibition by photographic artist Sara Angelucci titled Undergrowth. Asked how her work draws attention to the role of the camera both as a tool of colonization and a means of scientific inquiry she explains, “Photography had a profound hand in shaping the way we see the world—in qualifying and quantifying the world for consumption… microscopes, x-rays and telescopes were invented to expand our field of vision, and knowledge. The problem becomes what we do with this knowledge and how we use it to interfere with and try and control natural systems.” The exhibition features large-scale images of native and invasive plants interwoven which point to the intense impacts and struggle that endure as a result of colonization and persistent colonial attitudes. The series Nocturnal Botanical Ontario comes from her acute desire to comprehend and explore vulnerable habitats and our role in interrupting the natural balance; it documents the vegetation surrounding her home and studio in the Pretty River Valley, part of the Niagara Escarpment. In her essay, Curator Shannon Anderson describes Angelucci’s process: “Working at night, she documents her immediate environment when it is most elusive, using a scanner to illuminate the plant and insect life thriving under cover of darkness. The large-scale prints created from this process reveal an intricate web of tangled growth, fallen seeds, and insects shining against a black background. Glowing like the cosmos, the microscopic and the macroscopic collapse into a singular, dense, and intricate plane of vision, expressing ideas of interconnection and cyclical change.” The exhibition opens at the TOM on June 3 and continues to August 26.

Ultimately, what we can do is to learn, work together, plant and harvest in ways that promote sustainability and healing, remember to give when we take, honour and respect the land, only take what we need, waste nothing, share gratitude, and remember that gardening is a way to connect with our mother, earth. As Kimmerer points out in her book, in some Indigenous languages, the term for ‘plants’ translates to “those who take care of us.” It would seem it’s our turn, to take care of them.

Wild Garlic Mustard Pesto

Wild garlic mustard—introduced from Europe as a food plant, it has become a great danger to forests and pollinator habitats across North America due to its invasiveness and the fact that it’s not edible for local wildlife or insects. One way to help stop the spread of this plant is to pull it up by the root in early-to-mid spring and use the leaves to make a pesto. You can also add it to salads and soups. It is easy to find growing along trails, riverbanks, and forests and is identified by its four-petal white flowers that cluster, leaves which are scalloped and smell faintly of garlic when crushed, and the root which takes the shape of an “S” or “L” shape when pulled.

INGREDIENTS

2 cups olive oil

8 cups garlic mustard leaves

20 leaves of fresh sage leaves

8-10 cloves garlic

3/4 cup pine nuts or walnuts

1 cup Parmesan

Four Squeezes of lime

METHOD

Add all ingredients to a blender or food processor and blend.

Sara Angelucci is a Toronto-based artist working in photography, video, audio and installation. Her projects are drawn from a range of personal photographs and films, to anonymous and found images. Based in the history of photography—from vernacular snapshots to professional studio portraiture—the history outside the image frame informs the direction of her research into natural and social histories implicated in the photograph. Photography’s material evolution and its shifting social influence provide rich ground for aesthetic interpretation, and inspire a range of materials and references that traverse her projects. Since 2013 her projects have focused on our fraught relationship with the natural world, channeling personal and environmental grief. Sara Angelucci completed her BA at the University of Guelph and her MFA at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. She is an Adjunct Professor in Photography at the School of Image Arts Ryerson University and is represented by the Stephen Bulger Gallery in Toronto. sara-angelucci.ca