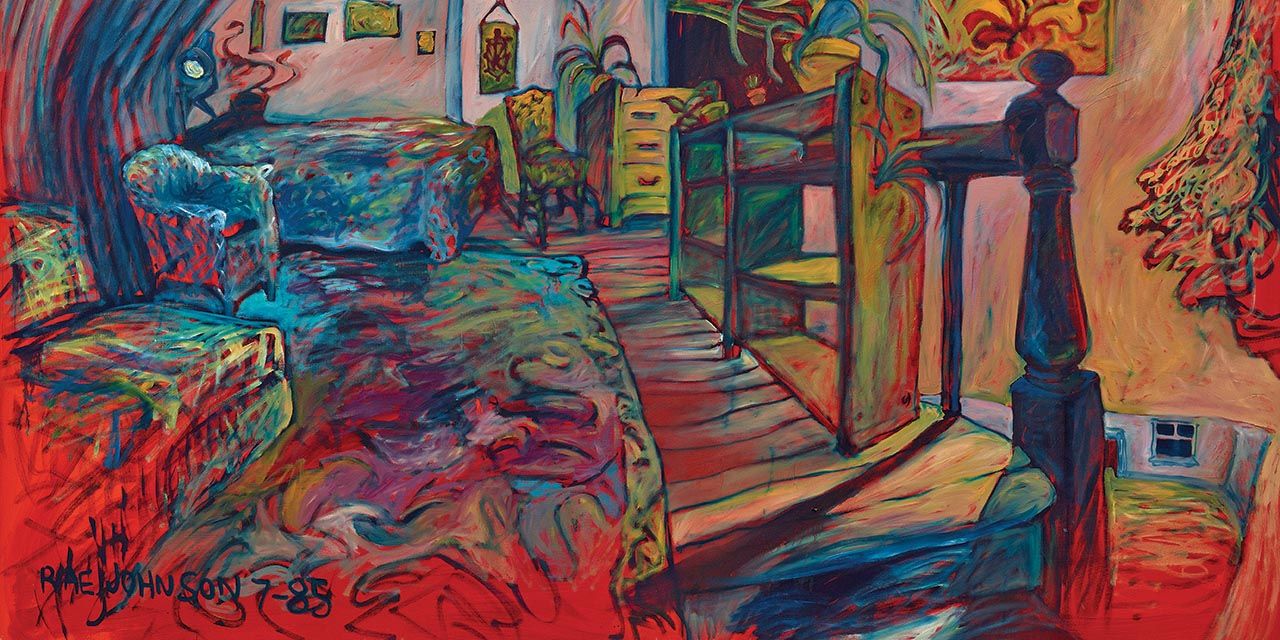

Rae Johnson, Red Interior, 1985. Oil on canvas, 165 x 266 cm. Gallery purchase with Matching Wintario Grant, 1992.

HIGH WINDOWS:

Legacy of the Tom Thomson Art Gallery

By Aidan Ware | Images courtesy of the Tom Thomson Art Gallery

From its Centennial beginnings in 1967 to its present-day role as a vital cultural institution, the Tom Thomson Art Gallery reflects six decades of artistic legacy, community vision, and national identity.

In the radical, turbulent, radiant summer of 1967, a small Canadian city located on the shores of Georgian Bay gave birth to what would become one of Canada’s most significant regional art institutions: the Tom Thomson Art Gallery. Founded as a Centennial project in Owen Sound, Ontario, the gallery was established in honour of Tom Thomson—a revolutionary painter whose works would become a cornerstone of Canadian cultural identity.

The legacy of Tom Thomson is not only in his art—it is also in the mythology that surrounds his life and death. Born in Claremont, Ontario, and raised near Owen Sound, Thomson developed his influential and iconic style of painting during his frequent trips to Algonquin Park, beginning in 1912 and continuing until his untimely death in July 1917, when his body was discovered in Canoe Lake under mysterious circumstances. Officially ruled an accidental drowning, speculation has persisted for over a century about the cause—was it suicide, murder, or misadventure? This enduring mystery only amplifies Thomson’s iconic status in the Canadian imagination—a symbol of raw nature, artistic genius, and unanswered questions. His death, like his art, invites contemplation about the Canadian landscape and the complexities of the human spirit.

“…I know this is paradise Everyone old has dreamed of all their lives— Bonds and gestures pushed to one side Like an outdated combine harvester; And everyone young going down the long slide To happiness, endlessly… And immediately Rather than words comes the thought of high windows The sun-comprehending glass, And beyond it, the deep blue air, that shows Nothing, and is nowhere, and is endless.” (Philip Larkin, High Windows excerpt, 1967)

Considering art within the social and political contexts of the times in which it was created provides us with a path to a deeper understanding of its message and meaning. Exploring the broad artistic, social, and political environs of the years in which the Gallery was founded reveals a period of saturated complexity and transformation.

Completed in 1967, High Windows by poet Philip Larkin was one of the seminal pieces of poetry written during the legendary Summer of Love. It references middle-aged attitudes towards the younger generation and old customs being forsaken for new freedoms. It also expresses a powerful metaphor for the transcendence of the human mind and consciousness toward an unfettered state of worldly abandon—perhaps an allusion to psychedelic experiences or to the psychological release from past norms into a new, uninhibited and dis-habituated philosophical and spiritual way of being. It stands as a powerful evocation of the tumultuous, lusty, and love-lost, shackle-shattering aesthetic of the times.

It was an era of revolutionary change on all fronts, filled with the vehemence of politics and yet a sense of extraordinary optimism. 1967 was undeniably a watershed year in Canada. It was the centenary of Canadian Confederation, and celebrations culminated at Expo 67 World’s Fair in Montreal. The National Gallery of Canada undertook an exhibition of 350 works of Canadian art spanning 300 years—the largest exhibition of Canadian art ever shown at the time. In politics, 1967 also saw the resignations of two prominent federal leaders: Official Opposition Leader John Diefenbaker and Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson. That year also marked shifts in youth culture, with hippies in Toronto’s Yorkville Village making headlines due to ongoing confrontations with police and City Council.

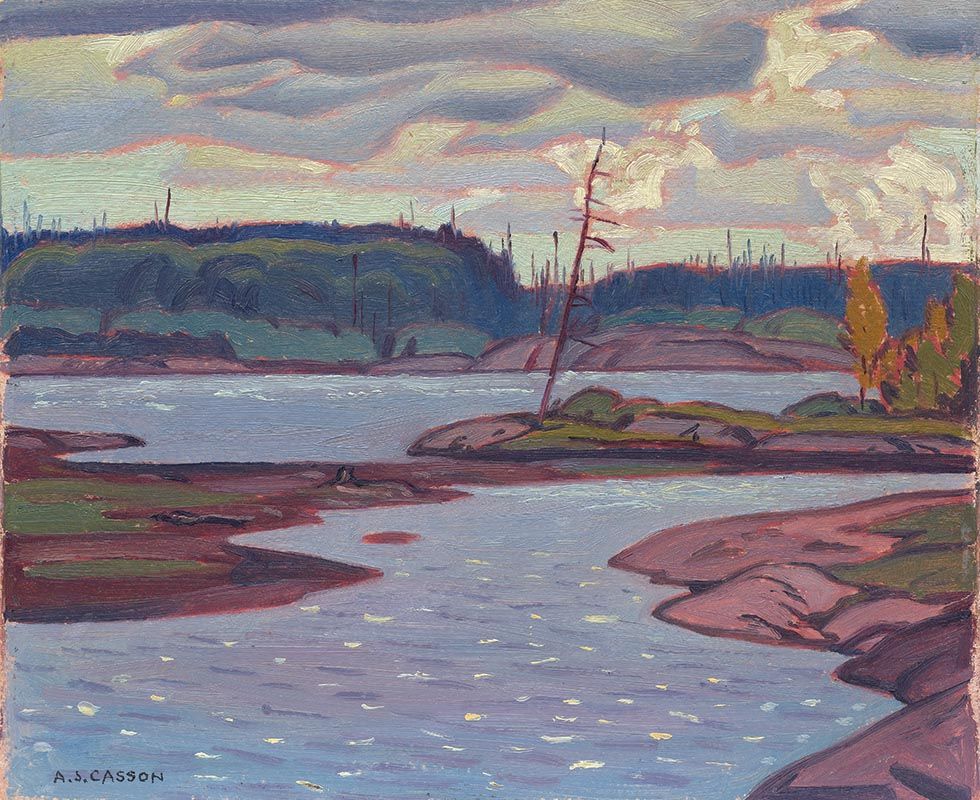

A.Y. Jackson, York River, Ontario October 1961, 1961. Oil on wood panel, 26 x 33.4 cm. Gift from A.Y. Jackson

By all accounts, Owen Sound was also in the fray of these times that were a-changin’, with a growing post-war population with divergent interests and tastes. Pictures from that time-period reveal bustling streets, burgeoning businesses, packed cafés, and a happening music scene. Styles of fashion and cars reveal a mix of squares and mods, with a balance of conservativism and a beat towards modernism. From out of the shadowy arches of old social archetypes and tropes, there was a large young population emerging with new ideas about gender equality and independence. It was also ten years since Owen Sound’s centennial which was not only one of the largest celebrations ever held in the region, but also served to provide a pivotal moment in which the identity of the city was more formally forged and honoured, a time when people connected to the core of the city’s heritage and aspirations.

In terms of art, 1967 in all its glory, celebration, and upheaval, set the stage for radical re-thinking, curatorial expansion, and the formation of new organizations across the country. In 2017, Doug Saunders wrote, “Once the bucket of Canadian identities had been kicked over by 1967’s spasm of centennial joy, a cascade of new realities, new ideas, new institutions and new ways of living came flooding out. Fifty years later, we are still awash in their novelty. We are the children of 1967, the entirely new people who came out of that container.”

Indeed, the Tom Thomson Art Gallery was one of those institutions birthed from that container. Its origins trace back to The Lyceum Club and Women’s Art Association of Owen Sound, which purchased three oil sketches in 1929 from the Thomson estate and displayed them in public buildings until the Gallery was established. The original home of the Gallery was a church purchased by the Grey County Historical and Art Society in 1959. Eight years later, in 1967 the City of Owen Sound ratified construction of the Gallery as a Centennial project and officially opened the Tom Thomson Memorial Art Gallery.

Upon learning of the plans for an art gallery in Tom Thomson’s honour, Group of Seven member A.Y. Jackson famously remarked “I think this thing is of too great an importance to miss” – a statement that would later become memorialized in a tribute sculpture by artist Micah Lexier with those words in laser cut steel placed on the roofline of the Gallery.

Born into a changing world, the Gallery was anchored by the passion of the Historical and Art Society, which between 1959 and 1965 stewarded several pivotal donations that formed the foundation of what is now a 2,600+ piece collection of historical and contemporary Canadian art.

Twenty-five artworks by Tom Thomson were donated during those formative years by members of his family, establishing the core of the Gallery’s Thomson collection. It remains the fourth-largest public collection of Thomson’s work in Canada and the only collection built solely through direct connections with his family and friends – a legacy that continues to this day. In 2025, the Gallery received a remarkable bequest of 3 Tom Thomson oil sketches from Gloria M. and James E. Smith of Toronto which were originally gifted by Tom Thomson’s mother, Margaret Thomson, to her niece Charlotte (“Lottie”) Tripp Gilchrist, who was raised closely with the Thomson family in Leith. Passed down through generations, they have now found a permanent home in Owen Sound.

A.J. Casson, Deer Lake, 1967. Oil on plywood, 22.5 x 27.5 cm. Gift from artist

Thomson, the Group of Seven, and their contemporaries were only the beginning. The expanding collection continues to explore their lasting influence, as living artists offer new perspectives on the Canadian landscape and current issues. Among them, Bognor artist George McLean stands out for his masterful depictions of wildlife in natural habitats, combining technical precision with a deep reverence for the Grey County environment. His work builds upon the legacy of Canadian landscape painting while expanding its scope to include the intricate and intimate lives of the animals that inhabit it. Similarly, Flesherton based artist Rae Johnson reimagined the landscape through an expressionistic and often dreamlike lens, infusing it with emotional intensity and personal symbolism. Her work challenges traditional representations by layering memory, myth, and mood, offering a powerful, contemporary counterpoint to historic approaches.

Since 1967, the Gallery has been led by 10 directors, each contributing to its evolution. Reflecting on the Gallery’s emergence during such a complex cultural moment, and on its continuing commitment to the visual arts in Canada, is both a privilege and a meaningful act of interpretation. The collection invites visitors to explore the layers of time, trends, and artistic practices—to find connections, disruptions, and new resonances.

The works in the Gallery’s collection do not exist as lone specimens—they speak to each other. They reach out through time towards us—to captivate and corroborate, to conspire and conceive of new and old realities.

Ultimately, the story of the Tom Thomson Art Gallery is the story of people. Of those who, in 1959, believed in the value of art and ideas. Of the Thomson family, who gave his work to the city. Of the hundreds of donors, staff, volunteers, and the thousands of artists who have participated in shaping the Gallery’s legacy. And it’s the story of the many, many visitors who have come through its doors—to find, to share, to see.

Art matters. It matters because it takes on the biggest conversations of our times – whether that’s oppression, genocide, racism, sexism, the environment, aging, or the pandemic. The language of art is the landscape of our lives and it’s personal. It’s social. It’s political. It’s human.

As we reflect on nearly six decades of vision, generosity, and cultural stewardship, the Tom Thomson Art Gallery stands not only as a monument to one of Canada’s most enigmatic artists, but as a living, evolving testament to the power of art in public life. Rooted in history, yet always reaching forward, the Gallery invites us into dialogue—with the land, with one another, and with the stories still unfolding.

In the enduring mystery of Thomson’s life and death, and in the vibrant legacy he inspired, we are reminded that art is never static—it is a horizon, and a higher window, urging us to look deeper, think wider, and imagine endlessly. E